INTRODUCTION

Smoking rates remain disproportionately high among Chinese immigrants, particularly in males. In New York City (NYC), the city with the largest Chinese population in the US1,2, the current (past 30-day) smoking rate among Chinese American males is significantly higher than that among the general male population (28.2% vs 17.5%)3. Foreign-born Chinese Americans (representing 72% of Chinese American population in NYC)4 are more likely to smoke than their US-born counterparts3.

The persistent high smoking rate among Chinese immigrants is in part due to the low intention to quit and underutilization of evidence-based smoking cessation services such as telephone quitlines and in-person counseling programs5,6. Studies among Chinese American smokers reported that 35–51% were not interested in quitting, and most of those who tried to quit relied on willpower without using any proven smoking cessation methods5,7-9. The low quit intention may be attributed to low health literacy about the harms of smoking5,9,10 and strong attachment to traditional Chinese social norms that support smoking in men11,12. The underuse of proven cessation methods may be explained by the dearth of culturally appropriate programs targeting this population13 and access barriers to available smoking cessation services14-16. Current smoking cessation programs, which focus on Chinese communities such as Asian Smokers’ Quitline (ASQ), and communitybased services have limited population impact due to their low engagement rates17.

Addressing tobacco-related disparities for Chinese immigrants and maximizing the impact of tobacco control among this population requires more understanding about their challenges in using available cessation services. It also requires innovative forms of interventions that can increase treatment reach and effectiveness. Mobile health (mHealth) strategies, such as automated text messaging or short message service (SMS) programs and social media-based (e.g. Facebook or Twitter) smoking cessation interventions are effective in promoting quit outcomes18-21, and can reach wide audiences and deliver time-sensitive support. Metaanalyses on SMS smoking cessation interventions reported that the interventions increased 7-day point prevalence abstinence (odds ratio, OR=1.38; 95% CI: 1.22–1.55)21 and 26-week abstinence rates (risk ratio, RR=1.67; 95% CI: 1.46–1.90; I2=59%)20. A systematic review of social media-based smoking cessation interventions (i.e. via Facebook, Twitter and WhatsApp) concluded that the interventions had promising preliminary effectiveness in increasing quit outcomes19. Therefore, SMS and social media cessation interventions may expand smokers’ access to smoking cessation treatment.

However, Chinese immigrants may primarily use WeChat, a multi-purpose social media app that is popular in China. Launched in 2011 by Tencent, WeChat has reached 1.2 billion monthly active users worldwide as of May 2020, ranking the 3rd most popular mobile messenger app worldwide after WhatsApp and Facebook Messenger22. Roughly 83% of smartphone users in China use WeChat23. Despite the widespread use in China, WeChat use pattern among Chinese immigrant populations in US remains unknown. The purpose of this study was to explore Chinese immigrant smokers’ quitting experiences, and their social media and mobile phone text messaging usage. Findings from this study may help inform strategies to improve engagement and effectiveness of smoking cessation interventions that focus on this racial/ethnic minority group that has high smoking rates and disproportionately lacks access to cessation treatment.

METHODS

From March through May 2018, we employed indepth interviews among 30 adult Chinese immigrant smokers in NYC. Using a semi-structured guide, we conducted in-depth interviews to explore their smoking cessation experiences, barriers to accessing and using available smoking cessation services, and experience using social media and mobile phone text messaging. Eligibility criteria for the in-depth interview included: 1) aged ≥18 years, 2) Chinese immigrants, 3) current smokers or former smokers who quit in the past 12 months, and 4) used WeChat in the past 6 months. We requested participants to have experience with WeChat because it would allow them to provide insights about what they like and dislike about WeChat, use patterns and more. Interviews lasted 30–55 minutes and were conducted in Mandarin, the official language of China. Interviews were audio-taped, transcribed verbatim, and translated into English.

Following the in-depth interviews, we developed a quantitative survey to assess Chinese immigrant smokers’ smoking patterns, quit attempts and intention, past-year use of cessation aids, and patterns of using social media and mobile phone text messaging. Eligible participants for the quantitative survey were Chinese immigrant current smokers aged ≥18 years, and they were not required to have ever used WeChat. A total 49 Chinese immigrant smokers completed the self-administered paper-andpencil survey in May and June 2018. Two of the 49 participants completed both the qualitative interview and quantitative survey.

Social media and text messaging use was assessed by asking ‘On average, how often do you use WeChat?’ and ‘On average, how often do you do the following things on WeChat: instant messaging to individuals; instant messaging in groups; read news/articles; post on the “Moments”; browse friend/family's posts; play games; transfer money or make payment?’. Answer options ranged from ‘several times a day’ to ‘never’. Participants rated the frequency of using WeChat, WhatsApp, Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, and mobile phone text messaging on a 1–7 visual analog scale (‘1’ labeled as ‘least frequently’, ‘7’ as ‘most frequently’), or chose ‘I don't use it’.

Participants were recruited via flyer postings and in-person contacts (snowballing) from Chinatown (Manhattan) and Flushing (Queens), two communities with high concentrations of Chinese immigrant populations in NYC. Participants received $50 for the qualitative interview and $15 for survey. Study protocols were approved by New York University Grossman School of Medicine’s Institutional Review Board.

Qualitative data were analyzed using NVivo 1224. An initial codebook of themes and subthemes related to research questions was created using inductive analytical techniques of qualitative data analyses25,26. Three team members reviewed the codebook, discussed the appropriateness of the themes and subthemes, coded a subset of randomly selected transcripts independently, revised the codebook by adding emergent themes and subthemes, resolved disagreements on the codes through iterative discussions to reach consensus and theme saturation. Two team members then independently coded all of the transcripts. Descriptive statistics summarized quantitative survey results (e.g. frequency and percentage) using Stata 14.227.

RESULTS

Qualitative findings

Participants (aged 19–61 years) included 6 females and 24 males, 3 former smokers and 27 current smokers. Four primary themes emerged, including low quit intention, challenges to smoking cessation, access barriers to available smoking cessation services, and prevalent WeChat use (Table 1).

Table 1

In-depth interview themes and illustrative quotations

Low quit intention

Participants were generally not interested in quitting smoking. While smokers were familiar with the generic health warning that smoking is harmful, most were uncertain about the exact harms of smoking and benefits of quitting. A common misconception was that quitting smoking would endanger smokers’ health rather than reduce their risks, particularly for those who have smoked for years. One person said: ‘Mao Zedong suffered from health issues after he quit smoking, so did Deng Xiaoping. These great men both had health problems after quitting’ (P8, male). Furthermore, smoking was regarded by many participants as the only way to cope with bad mood (e.g. homesick and loneliness) and stress. As firstgeneration immigrants, participants experienced a significant decline in the size of social circles because of immigration, and they generally worked long hours. These could increase their risks for depression and anxiety. But they did not know how to deal with bad mood and stress without smoking. Participants said: ‘I live on my own here in NYC. I smoke when I get homesick or have nothing to do’ (P15, male) and ‘I feel anxious when I don't do well. Smoking helps relieve my anxiety’ (P17, male). Male smokers described offering cigarettes to friends as an important social activity to establish and maintain social connections. One participant said: ‘For Chinese, we sometimes need to offer cigarettes to others in order to build relationships. So I have to smoke’ (P11, male). Finally, non-daily smokers tended to deny that they were addicted, which made them consider cessation as unnecessary.

Challenges to smoking cessation

The persistent social norms, such as offering cigarettes to friends and not feeling comfortable refusing offered cigarettes posed a major challenge for quitting. One smoker said: ‘All people around me smoke. I told them that I've quit. They said “Smoking one more cigarette is fine”. So it's impossible for me to quit’ (P4, female). The other challenge is the lack of strategies to cope with cravings, as a smoker said: ‘When I saw other people smoking, I could not hold it. Quitting made me feel sleepy so I relapsed’ (P26, male).

Access barriers to available smoking cessation services

Most participants did not know that smoking cessation clinics and quitlines such as ASQ were available, and had no information about treatment procedures or how to use the services. One person noted: ‘I've never heard about cessation clinics or quitlines. There is no information about their treatment procedures’ (P2, male). Participants expressed skepticism about treatment efficacy, as one smoker said: ‘You can quit by chatting with someone? I don't think it's gonna happen’ (P1, male). In addition, smokers perceived willpower as key to successful quitting and consider cessation treatment as noncomparable to a strong willpower. One person said: ‘My willpower can help me quit. I'd prefer not to use things like smoking cessation clinics or quitlines’ (P12, female). Moreover, participants’ busy life hampered them from attending smoking cessation clinics or ASQ. Smokers said: ‘It's burdensome to use cessation clinics and quitlines. You have to make phone calls, make appointments, and visit doctors’ (P26, male) and ‘People like us don't have time to visit cessation clinics or call quitlines. We get up at 8 am or 9 am, and then go to work. We don't return home until 10 pm or even later’ (P18, male). Finally, non-daily smokers thought that cessation services were designed for heavy smokers. Thus, they did not even consider using the services.

Prevalent WeChat use

Nearly all participants used WeChat on a daily basis. One smoker said: ‘Everyone uses WeChat. I feel like there is no way to keep a normal social life if you don't use WeChat’ (P17, male). Participants reported that WeChat voice messaging and voice/video call made communication ‘easier and more convenient’ (P3, male), and WeChat ‘Moments’ allowed them to easily ‘get updates about families and friends’ (P5, male) and ‘share personal joyful and torturous experiences with friends’ (P14, male). Participants also enjoyed reading articles and news through WeChat. One participant said: ‘Now I seldom read newspapers. I read news on WeChat every day’ (P24, male).

Participants generally had no concerns about WeChat, because the privacy setting allowed users to define who can view their ‘Moments’. One smoker said: ‘I think most Chinese have no concerns. Otherwise they would not post things like where they go, where they eat, or share their locations on the Moments’ (P4, female). Five participants expressed concerns like ‘I worry that Tencent would release users' information’ (P6, female).

Participants used mobile phone text messaging but on rare occasions. Few participants used other social media platforms. According to the users, text messaging was used only to contact non-Chinese or non-acquaintance, Facebook and Instagram to keep connections with non-Chinese friends, and WhatsApp to contact people living in Hong Kong. Participants compared WeChat and Facebook, and felt ‘more secure to use WeChat because it protects users' privacy’ (P6, female). One smoker noted: ‘On Facebook, everyone can see your posts. Whereas on WeChat, only confirmed friends can see your posts’ (P26, male).

Quantitative findings

Participants’ mean age was 47.9 years (SD=13.27) (Table 2). Most were males (80%) and were born in mainland China (94%). About 31% of participants completed primary or middle school, 43% completed high school, 8% received associate degree from college, and 18% received Bachelor’s or advanced degrees. Participants had lived in the US for an average of 10.3 years (SD=9.22). About 73% were married, and 63% were full-time employed.

Table 2

Sociodemographic characteristics and tobacco use among Chinese immigrant smokers (N=49)

| Characteristics | n | (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years), mean (SD) Gender | 47.9 | (13.2) |

| Male | 39 | (79.5) |

| Female | 10 | (20.4) |

| Place of birth | ||

| Mainland China | 46 | (93.88) |

| Other | 3 | (6.12) |

| Residence in the US (years), mean (SD) Education | 10.3 | (9.22) |

| Middle school or less | 15 | (30.61) |

| High school or vocational high school | 21 | (42.86) |

| High school or vocational high school | 21 | (42.86) |

| High school or vocational high school | 21 | (42.86) |

| Some college, no degree or associate degree | 4 (8.16) | (8.16) |

| Bachelor’s or advanced degree | 9 | (18.37) |

| Marital status | ||

| Married, living with spouse | 32 | (65.31) |

| Married, living apart with spouse | 4 | (8.16) |

| Never married or single | 9 | (18.37) |

| Divorced or widowed | 4 | (8.16) |

| Working status | ||

| Full-time employed | 31 | (63.27) |

| Part-time employed | 8 | (16.33) |

| Other | 10 | (20.41) |

| Age of smoking initiation (years), mean (SD) Current smoking status | 19.9 | (8.25) |

| Non-daily smoker | 7 | (14.29) |

| Daily smoker | 42 | (85.71) |

| Cigarettes per day, mean (SD) | 13.8 | (8.49) |

| Time to first cigarette after waking (minutes) | ||

| <5 | 16 | (32.65) |

| 6–30 | 14 | (28.57) |

| 31–60 | 6 | (12.24) |

| >60 | 7 | (14.29) |

| Don’t know | 6 | (12.24) |

| Quit attempt in the past 12 months | ||

| No | 27 | (55.10) |

| Yes | 22 | (44.90) |

| Quit methodsa (n=22) | ||

| Gave up cigarettes all at once | 7 | (31.82) |

| Cut down on cigarettes gradually | 15 | (68.18) |

| Visited smoking cessation clinics | 3 | (13.64) |

| Consulted other healthcare professionals | 4 | (18.18) |

| Used nicotine replacement therapy | 8 | (36.36) |

| Called a quitline | 0 | (0) |

| Read self-help materials | 3 | (13.64) |

| Read information through the internet | 4 | (18.18) |

| Used an e-cigarette | 2 | (9.09) |

| Quit intention | ||

| Have no plan to quit | 27 | (55.10) |

| Plan to quit within the next 6 months | 17 | (34.69) |

| Plan to quit within the next 30 days | 1 | (2.04) |

| Trying to quit now | 3 | (6.12) |

| Ever use of alternative tobacco productsb | ||

| E-cigarette | 16 | (32.65) |

| Waterpipe | 5 | (10.20) |

| Cigar | 9 | (18.37) |

| Chewing tobacco, snuff or dip | 3 | (6.12) |

| Snus or dissolvable tobacco product | 3 | (6.12) |

Most participants (86%) were daily smokers. Participants’ mean age of smoking initiation was 19.9 years (SD=8.25). On average, participants smoked 13.8 cigarettes per day (SD=8.49). Among those who reported past-year quit attempts (45%), 55% used smoking cessation methods including 14% visiting a smoking cessation clinic. No one had called a quitline. Over half of respondents (55%) had no plan to quit smoking. Onethird of participants had ever used e-cigarettes.

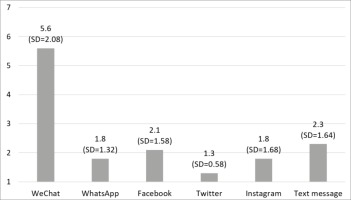

The majority (n=46; 94%) of participants used WeChat, including 90% daily users (n=44). WeChat was primarily used for social networking (80% daily browsing the ‘Moments’, 76% and 50% daily sending messages to individuals and in groups respectively) and information acquisition (67% daily reading news/articles; data not shown). Few participants used Facebook (n=11; 22%), WhatsApp (n=10; 20%), Instagram (n=5; 10%), or Twitter (n=3; 6%). All but one used mobile phone text messaging. WeChat was the most frequently used platform (5.6, SD=2.08) followed by mobile phone text messaging (2.3, SD=1.64) and Facebook (2.1, SD=1.58) (Figure 1).

DISCUSSION

This is among the few studies that investigated challenges in smoking cessation and barriers to accessing available smoking cessation services among Chinese immigrants, a disadvantaged group with high smoking rates and a lack of access to evidencebased cessation treatment. It is also among the first efforts to assess social media and text messaging use in this population. Our study affirmed the low quit intention among Chinese immigrant smokers5,8,9 and provided insights into why they were not interested in quitting. Smokers were not entirely clear about the risks of smoking. Consistent with prior studies11,15, the misconception that quitting smoking would lead to health problems is common. Although the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has invested in large scale anti-smoking media campaigns, most have not targeted Chinese Americans28. This may explain their low awareness about the harms of smoking. Future interventions should not assume this knowledge among this population and need to include information about how exactly smoking harms the body and what specific benefits people would gain from quitting.

Consistent with prior research11,12,14,15, our findings highlight the prominent role of customs that support offering cigarettes to friends and norms that create discomfort in refusing, as a major barrier to quitting. Male smokers practiced this custom to maintain social networks. Encouragingly, participants acknowledged that this custom is less pervasive in the US, indicating that smokers may be sensitive to the American anti-tobacco societal values. Future cessation programs targeting Chinese immigrant smokers need to provide skill training in refusal strategies. Messages emphasizing considerations for others’ health and cessation decision may help reframe the cigarette offering culture.

The lack of stress management skills also explained Chinese immigrant smokers’ low quit intention. As first-generation immigrants, smokers often worked long hours and had limited social support due to language barriers and the decline in social circle size. These factors posed elevated risks for depression and anxiety. Without stress coping capacities, many chose to ignore the adverse health effects and continue to smoke. Smoking cessation programs targeting this population should provide training in stress management.

Smokers, including men and women, encountered similar access barriers to available smoking cessation services, including their low awareness about the services, doubt of treatment effects, misconception about the effect of willpower, and time constraints. Educational campaigns that inform people about the proven cessation methods, their treatment procedures and efficacy, and encourage smokers to try those methods as a complement to willpower may promote the uptake of proven cessation methods. Moreover, Chinese immigrant smokers may be reluctant to use counseling therapy (e.g. smoking cessation clinics and quitlines) for making behavioral changes16. Studies are warranted to explore innovative forms of smoking cessation treatment that promotes engagement among this population.

Non-daily smokers’ perceptions about addiction played an important role in their cessation decision making. They tended to deny addiction and believed that cessation services are designed for heavy smokers. Thus, they did not even think about quitting or seeking cessation assistance. Findings suggest that Chinese immigrant smokers may not fully understand nicotine dependence. Future research is warranted to understand how Chinese smokers conceptualize addiction. Smoking cessation programs need to include discussions about risks and symptoms of addiction.

As an important social networking tool and primary source of information and entertainment, WeChat was the most frequently used social media platform among Chinese immigrant smokers. Other platforms and mobile phone text messaging were rarely used. WeChat’s prompt and convenient communication features allowed people to maintain close interactions with families and friends. The recreational feature (e.g. reading news/articles) caught people’s attention whenever they felt bored or craved for distractions. Most participants had no concern about WeChat. Few expressed their concern about Tencent’s capacity to protect user information. Such concern is common for most social media platforms. Given the prevalent use, WeChat has potential to serve as an easily accessible platform for delivering smoking cessation treatment among Chinese immigrant smokers. To our knowledge, no study has been conducted in the US to explore using WeChat in tobacco control outreach or treatment programs. A few studies have been carried out in China to evaluate WeChat-based smoking cessation treatment, but efficacy remains unknown29. Future research is necessary to investigate the feasibility and effectiveness of using WeChat to engage Chinese immigrant smokers and deliver smoking cessation treatment.

Limitations

Findings should be interpreted with caution. First, our sample was relatively small, and participants were recruited from two communities in NYC. Thus, we cannot assume the findings to be broadly representative. Second, qualitative interviews were conducted in Mandarin. Thus, beliefs and experiences of Cantonese-speaking smokers and those who speak other dialects were not captured. However, the majority of Chinese immigrants in NYC can speak Mandarin even if their primary language is Cantonese30. Third, our study was conducted before the COVID-19 crisis. Smokers may have changed their smoking behaviors since the outbreak of the pandemic because coronavirus poses for smokers an increased risk of serious pulmonary complications compared to non-smokers. A recent meta-analysis reviewed 19 studies and concluded that smoking was associated with higher odds of progression in COVID-1931.

CONCLUSIONS

This study has important implications for future research. Given the prevalent WeChat use, research is warranted to explore the feasibility and efficacy of using WeChat for smoking cessation treatment targeting Chinese immigrant populations. Moreover, treatment programs for Chinese immigrant smokers must address their low awareness about risks of smoking, correct misconceptions about cessation and willpower, reframe social norms around smoking and offer training in stress and craving management skills and refusal strategies.