INTRODUCTION

Worldwide, tobacco use remains one of the most important causes of morbidity and premature death1. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), about 30% of the world’s total population uses tobacco in some form1. Also, tobacco smoking contributes to six out of the eight leading causes of mortality worldwide1. Although the consequences of tobacco smoking on health are slow and gradual, tobacco smoking remains an important risk factor for coronary artery disease, cerebrovascular disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and cancers of various organs such as lungs, larynx, oesophagus, oral cavity, and pharynx2. Moreover, smokers tend to experience greater productivity losses and suffer greater levels of impairment than non-smokers3.

While cigarette consumption continues to decline in high-income countries (HICs), its use is rising in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs)4. This has been attributed to the tobacco industry deliberately targeting LMICs due to their potential as newly emerging markets4,5. The increasing global burden of tobacco has necessitated several concerted efforts to control its use4. The World Health Assembly, therefore, approved the WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (WHO/FCTC) in 20031, formulated to ensure a global partnership to mitigate a global tobacco epidemic using evidence-based best practices for tobacco control1. Expectedly, one of the important aspects of tobacco control is smoking cessation. Although, few smokers are able to quit smoking spontaneously, due to the addictive nature of nicotine4, tobacco cessation services are reported to increase the number of smokers who wish to, and eventually, quit smoking6. These quit intentions usually precede quit attempts, which may eventually be successful or otherwise.

In many countries in Africa, tobacco control is often not seen as a health priority due to competing demands for other pressing health problems7. Furthermore, the interference of the tobacco industry and related economic gains (taxes and employment opportunities) have hampered tobacco control; hence, tobacco cessation services are rarely available at the population level in many developing countries. Though studies have assessed quit intentions and attempts, determinants of quit attempts, and eventually tobacco cessation, these have been studied among sub-populations such as adolescents, undergraduates or patients8-16. Studies that have assessed quit intentions and attempts, in the general population, have mostly been in HICs17-21. The WHO advises that, in order to effectively reduce tobacco-related morbidity and mortality by 2030, combined prevention and cessation programs will achieve more than either intervention alone22. Although well documented in many HICs, there is limited evidence about cessation determinants and quit intentions in LMICs such as Nigeria. Furthermore, despite established benefits of application of behavioural theories to effect behavioural change, there has been no application of the transtheoretical model (TTM) to explore quit intentions in LMICs including Nigeria. This study, therefore, intends to describe the correlates of quit intentions among smokers in Nigeria using existing data.

METHODS

Study population and study design

The study was an analysis of secondary data from the 2012 Global Adult Tobacco Survey (GATS). The Global Adult Tobacco Survey (GATS) is part of the Global Tobacco Surveillance System (GTSS) developed by CDC (Centre for Disease Control) to provide global standards that systematically monitor tobacco use among individuals aged ≥15 years. Randomly selecting one individual per household, a total of 9765 individuals were interviewed. The overall response rate for GATS Nigeria was 89.1%. The household response rate was 90.3% (86.8% urban, 94.1% rural), while the individual response rate was 98.6% (98.0% urban, 99.2% rural). Data were collected on sociodemographic characteristics, household possessions, smoking history and quit intention history, and other variables.

Data analysis

Data for current smokers were extracted and analysed using Statistical Package for Social Sciences version 21 (SPSS). Descriptive statistics were done using means, proportions, tables and charts. Bivariate analysis was done to determine factors associated with smoking quit attempts, and the level of statistical significance was set at 5%. Binary logistic regression analysis was used to determine independent predictors of smoking quit attempts.

Quit intention stage

Based on the TTM theory, this was reported in three categories using responses to the question: ‘Which of the following best describes your thinking about quitting smoking?’. A ‘yes’ response to ‘I am thinking of quitting within the next one month’ was defined as ‘preparation stage’. A ‘yes’ response to ‘I am thinking of quitting after one month but within the next 12 months’ was defined as ‘contemplation stage’, while a ‘yes’ response to ‘I am thinking of quitting someday but not in the next 12 months’ was defined as ‘precontemplation stage’.

RESULTS

The mean age of respondents was 39.3 (±13.0) years. In addition, the respondents were distributed across the geopolitical zones of the country with the highest proportion from the Southwest (19.1%) and least from the Northeast (11.2%). Well over half of the respondents (71.8%) resided in rural areas, and the majority (95.4%) of the smokers were males. Over two-thirds (63.9%) were literate, about 8.9% of the respondents were unemployed, and 22.5% belonged to the highest quintile of wealth. Furthermore, 40.6% of the respondents had quit intentions in the 12 months preceding the survey. However, respondents who had tried to quit smoking were able to sustain the behavioural change for different durations. The mean duration of quit attempts was three months (±10 days). The most prevalent reasons for quit intentions were health concerns (31.0%) and family pressure (24.9%). Other reasons for quit intentions were harm to others (20.3%), disapproval by friends (13.1%), cost (8.9%), and their jobs (4.4%). Only 14.7% of the respondents who had quit intentions had some form of support. Those who used nicotine gum or patch accounted for 2.7%, while 3.7% used other prescription medication. In addition, 5.4% of those who had support used herbal/traditional medicines, while 10.0% used smokeless tobacco. None of the respondents had been able to access a quitline (none was available at the time of data collection). Moreover, about 27.0% of respondents had visited a doctor or healthcare worker in the past 12 months for general health complaints. During the visits, 66.4% were asked if they smoked and 90.9% had been advised to quit smoking by the healthcare provider. Furthermore, in the 30 days preceding the survey, 56.4% of respondents had noticed health warnings on cigarette packs and 40.5 % of these had started thinking about quitting smoking. Most respondents (64.8%) were in precontemplation stage, with 20.3% in contemplation stage, and 14.9% in preparation stage. Across the geopolitical zones in Nigeria, there were varying numbers of smokers in the three quit-stages as previously defined. Smokers with the highest level of education constituted a high proportion (80.7%) of those in precontemplation stage. Furthermore, smokers who had the highest level of education had the lowest percentage of smokers (2.6%) in the preparation stage. Smokers who were government employees were mostly in the preparation stage (14.4%) while fewer smokers working in the private sector were in the preparation stage (34.5%).

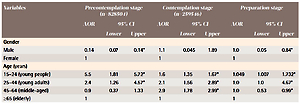

Furthermore, a smoker who was likely to make quit attempts was likely to be male (40.7%), reside in an urban area (45.3%), be over 65 years old (58.8%), have no formal schooling (52.2%) or be a government employee (41.9%). Shown in Table 1 are the adjusted predictors for smokers in the three quit-stages. Respondents who were aged 45–64 years were over 2.5 times more likely to make smoking quit attempts in the next 12 months compared to those aged ≥65 years (OR=2.907; 95% CI: 0.776–2.993). Respondents with no formal education were about 60% less likely to make smoking quit attempts in the next 12 months than those with tertiary education (OR=0.662; 95% CI: 0.587–0.994). Interestingly, respondents who had seen health warnings on cigarette packs were less likely to make smoking quit attempts in the next 12 months compared to those who did not see them (OR=0.533; 95% CI: 0.242–0.988). Male respondents were less likely to contemplate quitting someday compared to females (OR=0.143; 95% CI: 0.070–0.140). Likewise, respondents who were aged 15–24 years were about 5 times more likely to contemplate quitting smoking someday compared to those aged ≥65 years (OR=5.497; 95% CI: 1.807–2.723). Respondents with no formal education were 50% less likely to make smoking quit attempts someday than those with tertiary education (OR=0.513; 95% CI: 0.243–0.990). Unemployed respondents were about 2.5 times more likely to contemplate quitting the habit someday compared to the government employees (OR=2.223; 95% CI: 2.122–2.329).

Table 1

Predictors of stages of quit intention among current Nigerian smokers

| Variables | Precontemplation stage (n=828504) | Contemplation stage (n=259546) | Preparation stage | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AOR | 95% CI | AOR | 95% CI | AOR | 95% CI | ||||

| Lower | Upper | Lower | Upper | Lower | Upper | ||||

| Gender | |||||||||

| Male | 0.14 | 0.07 | 0.14* | 1.1 | 0.045 | 1.89 | 1.0 | 0.05 | 0.84* |

| Female | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||||

| Age (years) | |||||||||

| 15–24 (young people) | 5.5 | 1.81 | 5.72* | 1.6 | 1.35 | 1.67* | 1.049 | 1.007 | 1.732* |

| 25–44 (young adults) | 2.4 | 1.26 | 4.57* | 2.1 | 1.56 | 2.89* | 1.0 | 1.0 | 4.67* |

| 45–64 (middle-aged) | 0.9 | 0.37 | 1.33 | 2.9 | 1.78 | 2.99* | 1.0 | 0.53 | 0.99* |

| ≥65 (elderly) | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||||

| Place of residence | |||||||||

| Rural | 0.7 | 0.47 | 0.96* | 0.9 | 1.54 | 4.95* | 0.45 | 0.28 | 1.29 |

| Urban | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||||

| Educational status | |||||||||

| No formal education | 0.5 | 0.24 | 0.99* | 0.6 | 0.58 | 0.99* | 0.5 | 0.25 | 0.84* |

| Primary education | 0.6 | 0.35 | 0.76* | 1.0 | 0.92 | 1.00* | 0.6 | 0.39 | 0.93* |

| Secondary education | 0.9 | 0.62 | 1.55 | 1.5 | 1.34 | 3.27* | 1.0 | 0.77 | 1.97 |

| Tertiary education | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||||

| Wealth index | |||||||||

| Poor | 1.5 | 0.85 | 1.72 | 0.9 | 0.07 | 1.09 | 0.6 | 0.54 | 1.85 |

| Middle | 0.7 | 0.57 | 1.37 | 0.8 | 0.19 | 1.41 | 0.6 | 0.33 | 1.14 |

| Rich | 1.3 | 0.68 | 1.89 | 0.6 | 0.29 | 2.17 | 0.9 | 0.70 | 1.23 |

| Richest | 1.7 | 0.81 | 2.52 | 0.5 | 0.48 | 3.89 | 0.6 | 0.45 | 2.06 |

| Poorest | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||||

| Marital Status | |||||||||

| Not currently married | 1.2 | 0.99 | 1.32 | 0.3 | 0.13 | 1.95 | 0.6 | 0.34 | 1.11 |

| Currently married | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||||

| Exposure to health warning | |||||||||

| Yes | 1.5 | 0.66 | 0.94* | 0.5 | 0.24 | 0.99* | 1.02 | 0.47 | 0.96* |

| No | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||||

| Had seen anti-tobacco message | |||||||||

| Yes | 0.5 | 0.86 | 0.92* | 0.75 | 0.495 | 3.65 | 0.8 | 0.49 | 3.66 |

| No | 1 | 1 | |||||||

DISCUSSION

This study used the TTM construct to describe the predictors of quit attempts among current smokers in Nigeria. Most smokers record smoking quit intentions and multiple quit attempts. The multiple quit attempts highlight the difficulty most smokers have with accomplishing successful cessation as well as the importance of characterising individuals who at least attempt to quit, since they may be more likely to benefit from smoking cessation programs. The transtheoretical model helps by classifying smokers based on the stage of quitting, so targeted interventions can be provided to enhance quit rates.

There were more smokers in precontemplation stage than in contemplation and preparation stages. A study conducted among indigenous Australians who were smokers also reported that the majority of smokers were in the precontemplation stage23. However, this was in discordance with results from analysis of secondary data from the Korean National Health and Nutrition examination survey, where most smokers were in contemplation stage. However, in the studies cited above, the stage with the least respondents was the preparation stage, implying that many current smokers do not have intentions to quit. In many cases, quit intentions may be influenced by serious issues such as health concerns, family members’ disapproval or stricter tobacco control policies in the country, as documented in this study. For smokers in precontemplation, there is a need to assess their awareness and risk perception of the harms of smoking. Moreover, more of the smokers resided in rural areas than urban areas. More smokers residing in rural areas contrasts to the study by Palipudi et al.24 in 13 countries, where more smokers were in urban areas. The higher percentage of smokers in rural areas may be due to their perception of tobacco being harmless and use in traditional ceremonies10. There are different potential reasons for geographic differences in smoking prevalence in Nigeria. Some of these reasons include: religion, culture and tradition, social norms, varying socioeconomic status of the residents, the influence of media, and the role of the tobacco industry.

Although many of the smokers were male, there were few female smokers buttressing the fact that women are also smoking. From the 2012 GATS, 5.6% Nigerian adults aged ≥15 years currently used tobacco products: 10.0% men and 1.1% women. In all, 3.9% of adults (7.3% of men and 0.4% of women) currently smoked tobacco, and 3.7% of adults (7.2% of men and 0.3% of women) currently smoked cigarettes at the time in Nigeria. Most smokers being male may be because smoking among women is still not totally acceptable in Nigerian culture, despite urbanization.

Respondents who were single were less interested in quitting the smoking habit within the next 12 months compared to married respondents. Those who are married may consider quitting either due to pressure from their spouses or even their children. Also, more young people were in precontemplation stage. Youth generally are curious and mostly have no health concerns, so they are unlikely to be seriously considering quitting. Young people were less likely to be in preparation stage, perhaps because young people are curious, less likely to fully contemplate their choices, and subject to peer pressure25, therefore, preventing smoking initiation is a key intervention for the young. However, middle-aged people have more responsibilities and are more likely to be contemplative, accounting for why there were more middle-aged people in preparation stage.

Many of these smokers were also working-class age and more than half were literate. However, majority of those literate people had completed only primary school. Among male smokers who resided in rural areas, those who had completed tertiary education constituted the lowest percentage. Those smokers who have tertiary education have, most likely, relocated to the urban areas. Fewer smokers in rural areas were contemplating quitting. Smokers in rural areas can easily access cigarette sticks, which are affordable and available as single sticks25. Also, those in higher wealth quintiles had less quit intentions, which contrasts with the findings of Matthews et al.26 and Santiago et al.27. The association with socioeconomic status may be so, as those in the higher wealth quintiles may be social smokers who readily have access to quality healthcare. The rich can also easily afford tobacco and this may account for why they are less likely to quit smoking. While the poor may need to consider food or healthcare costs, which are mostly out of pocket, over smoking.

For those who had tried to quit smoking, they were able to quit for different durations. Their different quit durations may indicate that smokers may make multiple quit attempts before they achieve abstinence or relapse. The durations also indicate that different interventions will be required in addressing smokers in different categories. Smokers in Nigeria had used a few different methods to aid quitting. It was instructive to note that no one had used a quitline, few had used pharmacotherapy, and others used non-conventional methods. The importance of support for quitting was corroborated by Fiore et al.28 who documented the benefits of telephone help and pharmacologic interventions to aid smoking quits.

Exposure to anti-tobacco media messages was associated with increase in quit attempts among smokers in contemplation and precontemplation stages. The importance of anti-tobacco media messages is corroborated by Durkin et al.29 and Glynn et al.30. The consistent deployment of these messages via various channels will continue to provide support for quitting. While some smokers genuinely see smoking as a habit that has no adverse consequence, these messages will enlighten them. For those who have no quit intentions or unsuccessful quits, these anti- tobacco messages may give the motivation to try.

Surprisingly, increased knowledge about the harmful effects of tobacco was negatively associated with initiating quit attempts. Research has shown that knowledge does not necessarily translate to action. This finding is corroborated by studies from Balmford et al.25 and Adeyey et al.31. In addition, many, though aware of the harmful effects, have no quit intentions, such as healthcare workers who smoke tobacco. The lack of immediate adverse consequence and the addictive nature of nicotine may be responsible for knowledge without commensurate action.

Strengths and limitations

The findings are generalizable to Nigeria, however, more recent national level data from another survey such as GATS are required to compare with these findings and address gaps, which include novel tobacco products in the country and quitlines that are being developed. Furthermore, as the data were collected in 2012, they may not reflect the current status of tobacco use in Nigeria.

CONCLUSIONS

This study assessed the overall prevalence of quit intentions among smokers in Nigeria, as well as among men and women, with the higher quit intentions among men. The study also showed the social factors associated with smoking quit intentions in smokers across the country. Most smokers in Nigeria are in the precontemplation stage, suggesting that they are not considering quitting, and efforts should be targeted not just at preventing initiation, but also encouraging quitting. Also, a new survey is needed to evaluate the current tobacco control efforts. Increased access to quit support through trained professionals and pharmacotherapy are crucial for moving forward. To this extent, efforts to assist smoking quit attempts in Nigeria using targeted interventions should be put in place by the government, including quitlines, treatment support, and capacity building across socioeconomic and geopolitical divides, as well as the generation of national-level surveillance data on tobacco control.