INTRODUCTION

Use of new and emerging tobacco and nicotine products, such as waterpipe tobacco smoking (WTS, or hookah smoking) and electronic nicotine delivery systems (ENDS, or ‘e-cigarettes’), has been steadily increasing in the USA, especially among adolescents and young adults1-4. A nationwide examination by the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention found that, among high school students in 2014, the prevalence of current WTS and ENDS use was 9.4% and 13.4%, respectively, both higher than the prevalence of current cigarette use (9.2%)5.

The FDA Center for Tobacco Products has been given regulatory authority over these emerging forms of tobacco and nicotine in the US, but policymaking responsibility for regulating the sale and use of these products falls primarily to State and Local officials6. Pennsylvania is a valuable State in which to examine tobacco policies addressing WTS and ENDS because it is politically diverse, with a range of Democratic and Republican elected officials representing urban, suburban and rural communities. There are also well-established tobacco control advocacy groups and tobacco manufacturers/processors that may influence the development of legislation. Furthermore, according to the National Conference of State Legislatures, as of May 2016 Pennsylvania was the only State that had not enacted legislation prohibiting the sale of ENDS to minors7. Therefore, the purpose of this study was to survey members of the Pennsylvania legislature to assess knowledge of, attitudes toward, and likelihood to support future regulations pertaining to WTS and ENDS.

METHODS

Survey participants

Based on consultation with policy experts and a search of the committees of origin for bills that contained the words ‘electronic cigarette’ or ‘waterpipe tobacco’, we determined that members of the Pennsylvania House Health and Senate Health and Welfare committees would be most likely to consider tobacco policy bills. Thus, we selected members of these committees as our survey population. After initially mailing 36 surveys to committee members, we received statements from five individuals that they do not participate in surveys. In addition, one respondent resigned and three could not be reached for follow-up because they lacked email and fax capabilities. Our final survey population was 27 individuals. This study was approved by the University of Pittsburgh Institutional Review Board.

Survey design

We developed a comprehensive survey based on conceptual understandings from our policy document reviews8, practical insights from preliminary interview feedback and previous policy studies9,10. It included 51 closed-ended and four open-ended questions. Except for one question that asked respondents to rank substances according to priority for legislative action, all closed-ended questions utilized a visual analogue scale. Visual analogue scales are continuous measurement devices that are considered reliable and valid11. For each set of questions, 0 represented strongly negative answers (i.e. ‘strongly disagree’) on the one hand and 100 represented strongly positive answers (i.e. ‘strongly agree’) on the other.

First, we asked participants to rate their familiarity with WTS and ENDS devices and current policy regulations. To assess knowledge, we asked 14 true/ false items using the visual analogue scale described above, with 0 as ‘definitely false’ and 100 as ‘definitely true’. We also asked participants to answer two open-ended questions related to knowledge. Second, we asked participants to rank the importance of policy related to ENDS and WTS compared to policy concerning other addictive substances (eight in total), and to rate their level of agreement with five statements such as ‘Hookah smoking is a public health problem’. Third, we asked participants 15 questions about how likely they would be to take certain actions relating to WTS or ENDS in the next six months. We also asked participants to answer two open-ended questions about regulation.

Survey dissemination

Recognizing that this is a notoriously difficult population to assess12-14, we conducted multiple rounds of dissemination of the survey via mail, email, fax and phone. Experts with significant ties to the legislature also personally reached out to members of these committees.

Analysis

Researchers entered the data from each survey response under each participant’s unique ID number. The printed visual analogue scale was 10 centimeters, so to determine the numeric value of each answer a researcher measured where the respondent’s mark fell on the line to the nearest half-centimeter. During the recruitment phase, several policy changes occurred that affected the answers to certain questions; we eliminated these questions during our analysis.

Data were analyzed using Stata 1315. We calculated basic descriptive statistics for all closed-ended questions. For the true/false items, we defined a score between 0-10 as correct for the false items, and 90-100 as correct for the true items. To facilitate analysis, we converted these results to ‘mean correctness’ and ‘median correctness’. To calculate mean correctness, we used the actual mean for items that were true, and 100 minus the mean for items that were false. We used the same technique to calculate median correctness. Therefore, the closer the mean or median was to 100, the greater number of respondents answered the item correctly. For the open-ended questions, two researchers conducted a qualitative analysis using a grounded-theory approach. After three rounds of analysis and subsequent discussion, the researchers met with a supervising researcher to synthesize themes from the open-ended questions with the data from the closed-ended questions.

RESULTS

We received 13 completed surveys (48%). This response rate is considered excellent when conducting research with policymakers12-14. Two individuals were lost to follow-up, as they logged onto the online platform but did not complete the survey. Response rates were the same for both chambers (36%). Of the 13 respondents, 7 (54%) were female and 8 (62%) were Republican.

Survey analysis

On a scale from 0 (not at all familiar) to 100 (very familiar), participants rated their overall familiarity with WTS as 28 (Standard Deviation [SD]=15). This number was slightly higher for ENDS, with a mean of 50 (SD=13). For both WTS and ENDS, policymakers rated their familiarity of current public health data and regulatory standards lower than their familiarity with how these products are used.

Participants answered a mean of only 27% (SD=20%) of knowledge items correctly. Mean correctness was not significantly above or below 50 for 12 (86%) items, indicating that participants were generally unsure about the correct answer. For the items specific to WTS, participants answered a mean of 24% (SD=15%) correctly. Participants were slightly more knowledgeable about ENDS, answering a mean of 30% (SD=24%) of the items correctly. Qualitative analysis of open-ended items revealed the primary theme that policymakers felt that they had insufficient knowledge to make effective policy on both substances, although consistent with the quantitative results, participants felt slightly more informed about ENDS. The majority of participants requested general information about both products (Table 1).

Table 1

Verbatim responses to open-ended questions

For legislative priority of substance abuse, WTS was ranked eighth (least urgent), and ENDS was ranked fifth. Participants were least likely to agree that WTS is a public health problem, with a mean of 55 (SD=28). Participants had slightly more agreement that ENDS are a public health problem, with a mean of 65 (SD=28). In comparison, agreement that traditional cigarettes are a public health problem had a mean of 72 (SD=20), and prescription opioid painkillers had a mean of 92 (SD=15).

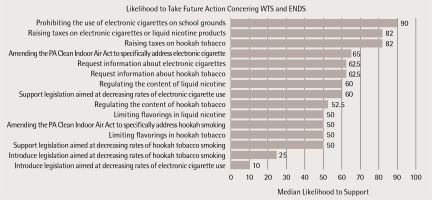

On a scale from 0 (not at all likely) to 100 (very likely), the median likelihood to introduce legislation aimed at curbing rates of WTS and ENDS use was 25 and 10, respectively (Figure 1). Democrats were more likely to favor raising taxes on WTS products (median=90, mean=84) and ENDS (median=90, mean=84) than Republicans (WTS: median=55, mean=52; ENDS: median=58, mean=56). Democrats were also more likely to support amending the Clean Indoor Air Act to include ENDS (median=90, mean=86) than Republicans (median=50, mean=51). When asked about barriers to regulation of WTS in an open-ended question, lack of knowledge again emerged as a theme, with five participants (42%) identifying it as the greatest barrier (Table 1). For ENDS, legislators mentioned the role of interest groups, such as privately-owned smoke shops most frequently (42%), followed by lack of information (25%: Table 1).

DISCUSSION

Despite the fact that tobacco use remains a leading cause of preventable death in Pennsylvania, this survey suggests that policymakers lack knowledge concerning newer forms of nicotine and tobacco products and consider them to be relatively low legislative priorities. Although our sample population was small and limited to Members of one State’s legislature, this study provides several findings that may be useful for public health practitioners and others engaged in public policy.

State policymakers in our study did not view the regulation of WTS and ENDS as a high priority when compared to other substances of abuse. This may be in part because other substances (such as opioids) have recently garnered substantial news media attention, making legislators more likely to act on them16. Moreover, we found that lack of knowledge of WTS and ENDS may contribute to legislative inaction. Thus, there is potential for public health entities to promote policymakers’ development of legislation via improved dissemination of information and increased exposure to effective educational material17.

In 1976, the Pennsylvania House of Representatives created a Legislative Office Research Liaison (LORL) to organize policymaking research support from the State’s public, State-related, and private universities. Over the years, LORL responded to thousands of legislative inquires, hosted hundreds of visiting scholars and published reports and policy research papers to support evidence-based policymaking in the Pennsylvania Legislature18. However, persistent State budget deficits led to the withdrawal of funding and closure of LORL in 200919.

New partnerships are needed to ensure that policymakers are informed of existing evidence in order to make informed policy decisions. These partnerships could be forged via traditional means (e.g. face-to-face meetings), or novel mechanisms such as online portals. One example of the latter is Web CIPHER, an Australian online portal that has demonstrated effectiveness in connecting policymakers with research updates and other tools to help them better access and engage with research20. Since policymakers in our study expressed a desire for more information about WTS and ENDS, such a portal might represent a novel way to disseminate this information to them in a timely fashion.

Limitations

Despite a complex protocol that involved multiple rounds of mailing, emailing and faxing the survey, we found it difficult to recruit policymakers to take part in our survey. Although our final response rate of 48% was higher than previous similar studies12-14, lack of enthusiasm for participation in survey research by policymakers remains an obstacle to conducting this research. Because of our small sample size, we were unable to conduct further analysis, such as stratifying according to party affiliation, which may have provided useful insight. In addition, we had to exclude some items in the initial survey due to the changing of laws and regulations that occurred while we were disseminating the survey. Finally, interpretation of the answers to the open-ended questions could be subjective, although we aimed to minimize subjectivity through multiple rounds of analysis and the use of a supervising researcher.

CONCLUSIONS

This study suggests that: 1) lack of knowledge of WTS and ENDS may contribute to legislative inaction from policymakers, and 2) policymakers do not view the regulation of WTS and ENDS as a high priority when compared to other substances of abuse. Improved lines of communication between public health experts and policy makers may be crucial to the development of policies that adapt to changing patterns of tobacco and nicotine use.