INTRODUCTION

Tobacco smoking, including secondhand smoke, is responsible for an estimated 8 million people prematurely dying each year and is the leading preventable cause of premature death worldwide1,2. Smoke-free policies are implemented to protect bystanders from secondhand smoke exposure and may help to denormalize and demotivate smoking3-6.

To regulate smoking in selected outdoor areas, local and national policies are being developed and implemented. In the Netherlands, outdoor areas of educational institutions are expected to be smoke-free since August 20207. In anticipation of this national smoke-free regulation and in collaboration with the municipal government, an inner-city outdoor smoke-free zone was implemented on 2 September 2019 in Rotterdam. The zone encompasses a university hospital, a university of applied sciences, a high school, and the public road in between. The smoke-free zone was not regulated by law but focused on creating a smoke-free norm using clear communication and signage, and via encouraging bystanders to address smokers who were smoking within the zone. Recently, we demonstrated that implementation of the smoke-free zone was followed by a 45% reduction in the number of smokers in the area8. At the same time, however, we noted that very few smokers were addressed when smoking within the smoke-free zone. Reluctance to address smokers has been noted by previous studies9-11.

Previous research showed that, although the proper addressing of smokers is a key factor for successful implementation of smoke-free zones12, many people feel uncomfortable to address smokers due to fear of negative responses13. In this study, we aimed to formally assess smokers’ responses to being addressed when smoking within the outdoor smoke-free zone. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) guidelines were used14.

METHODS

Design and setting

This observational field study was conducted in September 2019 at the grounds surrounding Erasmus MC, a tertiary hospital in Rotterdam, the Netherlands. The smoke-free zone encompasses the Erasmus MC, two educational institutions, and the public road in between. The zone is indicated with a blue line around it on the street and pavement and by ‘Smoke-free generation’ banners, signs and tiles (Supplementary file Figure S1). Using the momentum of the implementation of the smoke-free zone, observations were scheduled in the following month. In the first two weeks, representatives of Erasmus MC (‘addressors’) made rounds to address smokers. Depending on availability, these rounds were prescheduled twice a day for sixty to ninety minutes per round and varied in starting time. In pairs of two the authors (JB, JGtB, IB, LK) were observers from a distance of the addressors and smokers in the smoke-free zone. In the next two weeks, one observer acted as addressor, and the other as observer, following the same schedule as the addressors in the first two weeks. Neither the addressors nor the observers received specific training and no scripts were used. Addressors had the option to wear a Smoke-Free Generation vest, identifying them as Erasmus MC volunteers.

Data collection

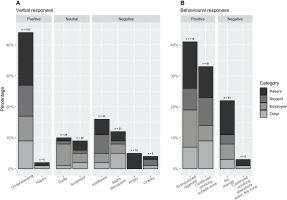

In both periods the observer noted the number of smokers present within approximately 5 m distance of the observers, whether they were addressed and if so, whether this was done directly or indirectly (i.e. smoker was able to overhear another smoker being addressed), the behavioral response to being addressed (positive: extinguished cigarette or continued smoking outside the smoke-free zone; negative: continued smoking at same location, or continued smoking elsewhere inside the smoke-free zone), whether the person addressing wore a Smoke-Free Generation vest and any verbal response (positive: understanding or happy; neutral: guilty or surprised; or negative: angry, cranky, indifferent, starts discussion). Smokers were not addressed if their cigarette was already extinguished or if they were on the phone. Any discrepancies among observers regarding the categorization of responses were discussed immediately until consensus was reached. Any other noteworthy events were recorded in a daily log.

Data analysis

Smokers were categorized into: patients, employees, students, and others, as described previously8. Categorical data are shown as numbers and percentages. Differences between groups were assessed using chi-squared tests.

RESULTS

In total, 331 smokers were observed. The majority were classified as patients (39%), employees (22%) or students (21%). Most smokers were addressed directly (73%), others indirectly (10%) or not addressed (17%). Among the latter group, responses were unobservable, and among the former data were missing for ten verbal and two behavioral responses. Observed verbal reactions were positive in 46% (n=121), neutral in 18% (n=48) and negative in 36% (n=96) (Figure 1). An understanding response was observed most often (n=121; 43%), employees more often respond guiltily (n=19; 73% of all guilty responses), whereas patients more often responded angrily than others (n=13; 87% of all angry responses). Verbal responses differed significantly across categories of smokers (χ2=29.3, p<0.0001). In the second period, more positive responses were observed than in the first (52% vs 31%; χ2=0.5, p=0.001).

The majority of smokers complied with the smoke-free policy after being addressed, by either extinguishing their cigarette (41%) or leaving to continue smoking outside the zone (34%). Behavioral responses differed significantly across categories of verbal responses (χ2=117.7, p<0.001; Supplementary file Table S1). Smokers who complied with the smoke-free policy (n=204), had a positive verbal response in 59%, a neutral verbal response in 24% and a negative verbal response in 17% of the cases. Almost all smokers who did not comply with the smoke-free policy (n=69) had a negative verbal response (n=62; 90%). There were no important differences in the proportion of smokers complying with the policy or having a positive verbal response according to whether those addressing wore a Smoke-Free Generation vest or not (79% vs 69%; and 41% vs 50%, respectively).

In the log, observers noted that they felt that smokers more often responded positively when being addressed in a positive (friendly and calm, e.g. ‘Did you know that this is a smoke-free zone?’) rather than a negative (judgmental) manner (e.g. ‘You are not allowed to smoke here’). Furthermore, they noted that if one person was smoking in the smoke-free zone, this appeared to attract other smokers. Finally, observers felt that addressing employees was easier than addressing students and patients, and that addressing a single smoker was easier than addressing a group of smokers.

DISCUSSION

In this study, addressing people who smoked insidea voluntary smoke-free zone often elicited a positive or neutral response and increased compliance with the smoke-free policy. Our findings are in line with previous research indicating that a positive approach towards smokers in a smoke-free zone more often results in a positive response15. Whereas fear of confrontation and aggression from smokers is a barrier perceived especially among healthcare staff11, our study indicates that this fear is often ungrounded.

The fact that representatives of Erasmus MC, among whom where members of the board, addressed smokers may have contributed to the successful implementation of the smoke-free zone, and also might explain the guilty response among many smoking employees. Clear signage in the smoke-free zone likely contributed to smokers’ awareness of the social norm16, possibly explaining the high proportion of understanding verbal responses. Changing the social norm in a smoke-free zone is a fundamental part of the implementation. Compliance with social norms increases with the number of others expecting a person to comply with the norm17. Culture plays an important role in this process, and it is unclear to what degree our findings are generalizable to other locations. However, we would like to argue that in any situation where smoke-free zones are implemented, changing the social norm is an important step. Addressing smokers can contribute to this, despite cultural differences. Furthermore, the addressors quickly gained experience in addressing smokers, which might have resulted in more positive responses of smokers being addressed. Combined with a positive approach, a positive response is likely. Finally, the indifference in the results when using a Smoke-Free Generation vest stresses that anyone can address smokers.

Strengths and limitations

The strength of this study lies within the repeated measurements on alternating days and times. Furthermore, during observations at least two researchers were present to ensure quick resolution of conflicting observations. It should be noted that those responding angrily to being addressed were often patients. A rather consistent group of smoking patients seated at a particular bench within the zone was addressed daily and this caused frustration. After several days it was decided to no longer address this group, which may have resulted in an underrepresentation of negative responses. However, including them would also be problematic as this group consisted largely of the same people every day. Double counting may have also occurred. Further limitations are the short timeframe between implementation of the zone and this study, and the homogeneity of addressors in the second two observation-weeks (e.g. female medical students).

Future research

More in-depth research is needed to assess how smokers actually experience being addressed, what they feel they need to adapt their behavior and why they feel a certain way after being addressed. Such information is an important step in developing recommendations for effective addressing and increasing compliance with voluntary smoke-free policies. Additionally, further research on how to strengthen self-efficacy of addressors is important, as the feeling that addressing smokers is easy, is an important predictor of doing so18.

CONCLUSIONS

Whereas many people may experience barriers to addressing smokers who smoke within a smoke-free zone, our study shows that addressing smokers often elicits positive responses and may help increase compliance with the smoke-free policy. A positive, calm and non-judgmental approach seems to be key in addressing. Our findings may help increase self-efficacy of those reluctant to address smokers in smoke-free zones.