INTRODUCTION

Goal 3 of The United Nations 2030 Sustainable Development Goals (SDG) focuses on good health and well-being, including efforts to reduce tobacco use. The engagement of the world’s 20 million nurses and midwives will be pivotal to meeting the SDG1-3, especially the target of reducing global tobacco use by 30% by 20304. Smoking remains a major contributor of all-cause mortality in Europe5,6, with a marked disparity in rates of tobacco use between Western and Central and Eastern Europe7,8. The involvement of properly educated nurses in the delivery of evidence-based tobacco dependence treatment could contribute to reducing these regional disparities9. However, there is a paucity of published research evaluating evidence-based strategies to educate nurses in tobacco dependence treatment, especially for nurses working in non-English speaking countries.

The WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (FCTC)10 Article 1411 highlights the need to educate all healthcare professionals to integrate cessation as part of standard care and encourage health professionals to offer a cessation intervention to all tobacco users in all encounters12. Nurses are uniquely positioned to implement Article 14 and offer cessation assistance to patients as they are in contact with patients, families and communities in a variety of healthcare settings13-15.

Educating nurses in Central and Eastern Europe about tobacco control

Education of nurses about tobacco control needs to consider both appropriate content and delivery methods and the 5As is an evidence-based approach that can be adapted across health settings12. Earlier efforts focused on educating nurses in the Czech Republic through a training of trainers (ToT) model. The content included tobacco use prevalence and health impact, principles of addiction, behavioural therapy, and evidence-based recommendations for cessation including the 5As approach and pharmacotherapy. It also included examples on how to approach patients. Three months after participation, nurses who attended the educational program were significantly more likely to provide patients who smoke with evidence-based cessation interventions compared to baseline1,12,14-16.

While the ToT model was successful, the number of nurses reached was limited. Therefore, the content was adapted into an online educational program with web-based country-specific resources for the Czech Republic and Poland, developed following a model successfully implemented in several states in the United States and two cities in China13,14,16-22. At 3 months follow-up, nurses were significantly more likely to provide smoking cessation interventions to patients who smoke and refer patients for cessation services than at baseline13. The purpose of this study is to describe the development and outcome of an online educational program provided to nurses in Central and Eastern Europe through the Eastern Europe Nurses’ Centre of Excellence for Tobacco Control. This work describes the first three years (2014–2017) of the Centre. The Republic of Moldova was added as a sixth country in 2017.

METHODS

Developing a Nurses’ Centre of Excellence in Tobacco Control

To scale up efforts to build nursing capacity for addressing tobacco dependence in Central and Eastern Europe, the Eastern Europe Nurses’ Centre of Excellence for Tobacco Control (hereafter referred to as CoE) was established in Prague, Czech Republic, in January 201423. The CoE is a partnership effort of the International Society of Nurses in Cancer Care (ISNCC) in collaboration with the Centre for Tobacco-Dependent of the 3rd Department of Medicine at the General University Hospital, Prague, with expert support from the Schools of Nursing, University of California, Los Angeles, and University of California, San Francisco. The CoE is hosted by the Society for Treatment of Tobacco Dependence, Prague.

The CoE’s goal was to offer nurses educational programs on evidence-based cessation interventions and engagement in tobacco control. The CoE offered technical assistance to partners in each of the five target countries: Czech Republic (CZ), Hungary (HU), Romania (RO), Slovakia (SK), and Slovenia (SI). This is a first multi-country Centre of Excellence focused on nurses and tobacco control.

Centre of Excellence development and planning

An initial step was to create a network of partners that could support the goals of the CoE, creating a Tobacco Control Advisory Group (TCAG), with representation from regional nurse and physician tobacco control experts, followed by identifying nurse leaders based upon existing relationships13,14,16,27. A quarterly newsletter (https://www.isncc.org/page/ COE), translated into all five languages facilitated information sharing among and within each country’s team. Each country received funding to provide stipends and support project activities.

The project team communications were facilitated through email and the creation of a web-based platform on the ISNCC website where all documents in the language of the country were uploaded and made available. In the first two years of the CoE, a total of 379 documents in the five languages plus English were uploaded. Materials also were housed on the Tobacco-Free nurses’ website.

Educational programs

Two methods were used to expand capacity: 1) in-person Training of Trainers (ToT) workshops, and 2) an online e-learning, including the development of country-specific web-based resources. Additionally, based upon the researchers experience in the US and because of the high rates of smoking among nurses in the region, focus groups were held with nurses who smoked and nurses who quit smoking to understand how to address this potential barrier for nurses’ engagement in cessation interventions25,26. The focus groups confirmed that nurses had several misperceptions about tobacco addiction. Nurses also expressed concern about engaging with patients who smoke and whether this could be a cause of stress for patients or for their rapport with the patients. Addiction, smokers’ willingness to receive advice, and best ways to start a conversation, were topics covered in the online education program.

The content of evidence-based educational programs was based upon an established evidence-based guideline for tobacco dependence treatment (i.e. the 5 As approach)12-14, and was reviewed by the Tobacco Control Advisory Group. Materials were translated, adapted and revised by experts from each of the five countries. Forward and backward translation of a sample, representing 20% of all materials in each of the languages, by nursing leaders assessed consistency of the content. A Manual of Procedures ensured fidelity in implementation of the CoE’s activities. Nurse-focused evidence-based clinical cessation intervention guidelines were developed for each country. These were printed and distributed through national nursing events, in participating institutions, and made available online. Ethics/Institutional Review Board (IRB) review and approval was obtained by the appropriate boards in each of the countries and the two US-based academic institutions, prior to the implementation of the online learning programs.

Training of Trainers workshops and seminars

Standardized one-day ToT workshops, based on the prior experience in the Czech Republic14,16, were implemented. The program covered a range of tobacco control areas, emphasising role-playing of cessation interventions and active engagement of participants14.

The ToT program was delivered by the country’s nurse leader, although a nurse leader from Czech Republic participated in the first two workshops held in each country to ensure fidelity of the implementation. Nurse leaders recruited participants through notices in their home institutions, contacts with nursing organizations, calling nursing directors in different healthcare facilities, and, in several instances, the nurse leaders received calls requesting the workshops. Participants received an electronic copy of all materials and an additional slide set for a short (45–60 minutes) seminar on cessation intervention that could be implemented in their home institutions. The ToT was an important step in identifying nurses who could then champion and support the online education components.

From 2014–2016, 753 nurses participated in a total of 37 workshops (Czech Republic 314, Hungary 167, Romania 106, Slovakia 99, Slovenia 67), surpassing the initial goal of 20 nurses per workshop. Three to six months after the workshop, participants were followed up with a phone call or email to assess what tobacco control-related activities they had initiated. At least 60% of the nurses surveyed had implemented an educational activity in their home institution, reaching an estimated additional 1000 nurses (based on respondents’ estimates), and also engaged in offering cessation intervention to patients, family and/or co-workers. As an additional outcome, one participating institution in the Czech Republic, changed its nursing assessment form to include routine assessment of tobacco use and documenting advice to quit, which prompted the need for additional education (i.e. short seminars) about using the 5As approach in that institution, thus reaching an additional 459 nurses.

Design of the online program evaluation

We used a prospective single group, pre-post design to assess the impact of the online educational program in increasing nurses’ self-reported implementation of cessation interventions, and self-reported changes in their attitudes towards tobacco control in five countries in Central and Eastern Europe.

Framework

The RE-AIM Model (Reach, Effectiveness, Adoption, Implementation and Maintenance) was used as a framework to guide CoE’s dissemination activities focused on nurses’ delivery of tobacco dependence treatment, providing benchmarks for evaluation24.

Reach – was defined as the number of nurses in each country involved in the educational efforts.

Effectiveness – was defined as the implementation of the evidence-based tobacco dependence treatment educational programs by the nurses in the various healthcare facilities.

Adoption – indicated the number of nurses who adopted tobacco dependence interventions as self-reported in their participation in the follow-up evaluation.

Implementation – referred to the increase in the proportion of nurses who self-reported consistently (usually/always) delivering a tobacco dependence treatment intervention after program participation.

Maintenance – was defined as evidence from reports from nurse leaders in each country about integration of tobacco dependence treatment in healthcare systems and other institutional and policy changes.

Participants

The goal for the online program was to recruit a purposive sample of nurses (minimum target of 500, or 100 per country), aged >18 years, who worked at least 50% of time, providing direct care to adult patients in each of the five target countries. Nurses who worked in paediatrics, and nurses who did not provide direct patient care were excluded. Nurses who did not provide an e-mail address for follow-up were also excluded. Additionally, nurses who did not complete the questions about cessation interventions (5As) were also excluded after initial completion of the baseline survey. The sample size target was calculated to ensure that we could detect differences from baseline to follow-up at 3 months, with a p<0.05 level of significance.

Online learning data collection

Recruitment and procedures

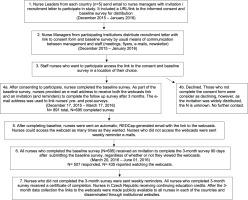

The procedures are described in Figure 1. As there was no upper limit on the number of nurses that could participate, the final sample size was larger than anticipated. However, the desired 100 per country was not reached. Countries where nurses’ access to online learning is just emerging, the level of engagement of nurse champions in each country and their preferences for online versus in-person learning, and national support for tobacco control, were all factors that may have influenced the discrepancy in sample size per country.

Survey instrument

The online baseline survey ‘Helping Smokers Quit’, a 28-item instrument assessed nurses’ cessation intervention practices, including recommending smoke-free homes. It also included items on nurses’ attitudes related to providing tobacco dependence treatment and two questions asked about their perception on the importance of nurses’ involvement in tobacco control (not reported). One item asked the nurses to estimate the number of patients counselled to quit tobacco in the previous week. The post-test also assessed usability, acceptability and accessibility of the e-learning programs. The online survey used REDCap™ (Research Electronic Data Capture), a secure, web-based data capture tool for data collection and management28. The consents, surveys and each of the 112 REDCap™ program keys (messages and warnings that pop-up during an online survey) were translated into each of the five languages. Data were collected in the period December 2015 to June 2016.

Intervention

Two webcasts were recorded using a prepared script in each country’s native language to ensure consistency and fidelity of the content, with variations only to accommodate country-specific data. One webcast focused on nurses and tobacco dependence treatment (45 minutes), the other on tobacco use cessation within oncology settings (30 minutes).

Data analysis

All data analyses used SAS 9.4. Demographic characteristics were presented as means with standard deviations or frequencies with per cent. For dichotomized outcomes, the significance level in change from baseline to follow-up was calculated using McNemar tests; while for all Likert-scale outcomes, the significance level for change from baseline to follow-up was calculated using Friedman tests. Generalized Linear Mixed Models were used for each dichotomized outcome to find predictors of consistently (defined as self-reported usually/ always) providing intervention. Each model included all possible predictors as well as an adjustment for country of origin.

RESULTS

Evaluation of the success of the CoE included an assessment of the number of nurses who participated in the education program and the nurses’ self-reported increase in the delivery of tobacco dependence intervention as well as any changes in their perception of nurses’ role in providing this intervention.

Online education program

Of the 891 nurses who answered the baseline survey, 695 nurses answered the questions on cessation interventions (i.e. 5As) and are included in the baseline analysis. The follow-up survey at 3 months was completed by 507 (73%) nurses (Figure 1). There were no significant differences at baseline between nurses who completed the follow-up and nurses who did not, thus it is unlikely that their absence created a systematic bias in the results.

Table 1 describes the country of origin, demographic and professional characteristics, and smoking status of the 507 participants with complete baseline and follow-up data; those with incomplete data were excluded from analysis. The majority (54.6%) of nurses were from the Czech Republic, female, had a diploma degree (69%), mean age of 43 years, and 20 years of practice. Sixty per cent were never smokers. The majority (85.8%) of nurses reported watching the webcasts, and of those who watched, 98% found the webcast on cessation intervention useful or somewhat useful, and 95% found the webcast on cessation for cancer patients useful or somewhat useful (data not shown).

Table 1

Demographics, professional characteristics, and smoking status of nurses who completed both the baseline and the follow-up survey at 3 months (N=507)*

Table 2 displays nurses’ self-reported smoking cessation interventions with patients at baseline and at 3 months post-participation in the online program. There was a significant increase in all 5A components, as well as an increase in reviewing patient’s perceived barriers to quitting and an increase in recommendations of advice for the creation of a smoke-free home environment post-discharge.

Table 2

Nurses self-reported frequency of providing smoking cessation interventions and recommending the creation of a smoke-free home, to patients at baseline and at 3 months post-participation in an online educational program (N=507)

| Intervention | Response of nurses | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| At baseline n (%) | At 3 months n (%) | pa | |

| Ask about a patient’s tobacco use | 0.01 | ||

| Sometimes/rarely/never | 150 (29.6) | 124 (24.6) | |

| Usually/always | 357 (70.4) | 380 (75.4) | |

| Advise a patient to quit smoking | <0.0001 | ||

| Sometimes/rarely/never | 174 (34.3) | 125 (24.6) | |

| Usually/always | 333 (65.7) | 382 (75.4) | |

| Assess patient’s interest in quitting | 0.002 | ||

| Sometimes/rarely/never | 210 (41.4) | 172 (33.9) | |

| Usually/always | 297 (58.6) | 335 (66.1) | |

| Assist a patient with smoking cessation | <0.0001 | ||

| Sometimes/rarely/never | 323 (63.7) | 257 (50.7) | |

| Usually/always | 184 (36.3) | 250 (49.3) | |

| Arrange smoking cessation follow-up | <0.0001 | ||

| Sometimes/rarely/never | 403 (79.6) | 361 (71.3) | |

| Usually/always | 103 (20.4) | 145 (28.7) | |

| Recommend the use of a telephone quitline for smoking cessation | <0.0001 | ||

| Sometimes/rarely/never | 379 (74.8) | 287 (56.7) | |

| Usually/always | 128 (25.3) | 219 (43.3) | |

| Recommend tobacco cessation medications | <0.0001 | ||

| Sometimes/rarely/never | 398 (78.5) | 336 (66.4) | |

| Usually/always | 109 (21.5) | 170 (33.6) | |

| Review barriers to quitting with patients unwilling to make a quit attempt | <0.0001 | ||

| Sometimes/rarely/never | 321 (63.44) | 234 (46.3) | |

| Usually/always | 185 (36.56) | 272 (53.7) | |

| Recommend creating a smoke-free home environment after leaving the hospital | <0.0001 | ||

| Sometimes/rarely/never | 268 (52.86) | 197 (38.9) | |

| Usually/always | 239 (47.14) | 310 (61.1) | |

There was a significant change in nurses’ agreement that they should be smoke-free role models from baseline to 3 months post-education (p=0.03, data not shown). There was also a significant positive change in nurses agreeing that it is important for nurses to be involved in tobacco control, even when compared to other disease prevention activities (data not shown).

There was a significant increase in nurses believing that they can increase the likelihood of a patient quitting through asking about their smoking status (Table 3), and a significant increase in nurses believing cessation intervention was an efficient use of their time, that patients appreciate their cessation advice, and that offering cessation support improves their relationship with patients. Additionally, there was a significant increase in the number of nurses that stated they needed more cessation training, but nurses at both points in time disagreed that they did not have time to provide quitting support to their patients.

Table 3

Changes in nurses from five Central and Eastern European countries self-reported attitudes and opinions towards providing smoking cessation intervention to patients at baseline and at 3 months after participation in an online education program (N=507)

At 3 months, significantly (p<0.0001) more nurses reported that they provided cessation intervention to one or more patients in the previous week, compared to no patients receiving an intervention. The proportion of nurses that responded ‘none’ to the question estimating how many patients they provided cessation support in the previous week was 36.4% at baseline decreasing to 25.1% at 3 months. The proportion of nurses that estimated that they provided cessation intervention to 3–5 patients in the previous week increased from 12% to 19% (data not shown).

Table 4 displays the predictors of nurses consistently (usually/always) providing cessation interventions to patients at 3 months post-participation in the online program. Nurses who were current smokers were 60% more likely to Assist and Arrange, and 83% more likely to Refer to a quitline compared to never smokers. Nurses who were former smokers were less likely than nurses who never smoked to Arrange for a follow-up.

Table 4

Predictors of consistently (usually/always) providing tobacco dependence treatment interventions 3 months after exposure to an online educational program change among nurses in five Central and Eastern European countries (N=507)

| Variable | Ask | Advise | Assess | Assist | Arrange | Refer to quitline | Recommend smoke-free home |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | |||||||

| Time | |||||||

| 3 months vs baseline | 1.30 (0.96–1.77) | 1.67** (1.23-2.72) | 1.41* (1.07-1.87) | 1.94** (1.45-2.59) | 1.76** (1.25-2.48) | 2.50** (1.85-3.40) | 1.90** (1.43-2.51) |

| Age | 1.01 (0.99–1.02) | 1.05** (1.03-1.07) | 1.02** (1.01-1.04) | 1.03** (1.01-1.05) | 1.05** (1.03-1.07) | 1.04** (1.02-1.06) | 1.04** (1.02-1.06) |

| Smoking status | |||||||

| Current smoker vs never smoker | 1.39 (0.87–2.21) | 1.17 (0.74–1.85) | 1.20 (0.80–1.82) | 1.60* (1.03-2.50) | 1.62* (1.01-2.61) | 1.83** (1.18-2.84) | 1.20 (0.79–1.82) |

| Former smoker vs never smoker | 1.03 (0.61–1.75) | 0.58* (0.35-0.97) | 0.72 (0.45–1.16) | 0.79 (0.46–1.33) | 0.34** (0.17-0.71) | 0.73 (0.42–1.26) | 0.70 (0.43–1.13) |

| Education | |||||||

| Non-baccalaureate vs baccalaureate or more | 0.81 (0.53–1.23) | 0.75 (0.50–1.14) | 0.75 (0.52–1.09) | 0.75 (0.50–1.13) | 0.49** (0.31-0.76) | 1.10 (0.73–1.66) | 0.57** (0.39-0.84) |

DISCUSSION

The CoE for nurses and tobacco control in Central and Eastern Europe was a pioneering initiative that has enhanced nurses’ access to education about evidence-based tobacco dependence treatment and tobacco control. By April 2019, all countries, including the Republic of Moldova, continued with their workshop activities, online learning and public events and are currently seeking additional funding. At country level, engaging with nursing leadership to support the online learning was pivotal to creating support for nurses’ role in tobacco dependence treatment. The creation of a support network of nurses that can champion nurses’ role in tobacco dependence treatment at the country level, while not the main objective of this paper, proved to be important in creating a multi-country support system that still exists.

The online educational program and web-based resources had a significant impact on nurses self-reported intervention with patients, confirming what others have found in clinical trials29. Additionally, it created a network of nurse champions who are poised to become leaders in tobacco control in their countries. Nurse champions have helped raise the profile of the importance nurses’ engagement in tobacco control through their efforts to promote the CoE within their own national societies and schools of nursing. The positive changes in nurses’ attitudes towards their role in tobacco control and how cessation can help instead of hindering their relationship with patients, was encouraging. It demonstrates that with proper information nurses are supportive of providing cessation interventions to their patients.

However, access to the online program was not uniform among the five countries. Nurses in Romania and Slovakia found it more difficult to participate, despite the efforts of the national nurse champions to encourage participation. Therefore, it is likely that in-person workshops, short seminars and online forms of education combined are necessary to ensure high levels of nursing engagement in cessation interventions.

The finding that nurses who were current smokers were significantly more likely to Assist and Arrange confirms that nurses are able to support patients quitting efforts, despite their own smoking status, although others have found that nurses who smoke were less likely to engage with patients. It indicates that the emphasis should be on educating nurses to provide excellent nursing care, including cessation support, as part of routine practice.

The RE-AIM was adequate to evaluate the development and impact of the educational program established through the CoE, but the duration of the initial years of the project might not have been sufficient to determine long-term maintenance of the program impact on nurses’ behaviour.

Limitations

The CoE’s development was not without challenges. Obtaining ethics board approval to allow collection of data in all institutions took time, and in some cases, it was the first-time approval given to a project lead by nurses. Therefore, even before the educational activities started the CoE promoted institutional changes in relation to the role of nurses in tobacco control and research. The lack of a control group limits the interpretation of the results as nurses may have self-selected to participate. The choice of not having a control group was based on the difficulty expressed by partners in withholding the educational program, even for the short time that it would take to collect follow-up data at 3 months. The nurses’ country of origin was not equally represented in the sample. This could be a reflection on the normalization of smoking cessation in the country, the scope of practice as well as nurses’ level of comfort in accessing an online learning platform. Czech Republic partners worked with their national nursing organization to provide continuing education credits to nurses who completed the program. This was the first accreditation provided to an online education program in the countries. Other countries’ partners participation was driven by the country partners and the other countries.

We did not track how widely disseminated was each of the materials produced. Nurses had access to the webcasts for the 3 months and may have accessed them more than once. In some of the countries, the nurse managers organized a group viewing of the webcasts as part of nursing education and we have no information on how many nurses watched the webcast in this manner. In addition to uploading materials such as newsletters on the websites, some were mailed to participating institutions and organizations. At the end of the data collection, the online learning was available to be placed on the websites of participating institutions as well. Therefore, it is possible that there was a reach that was not captured by the evaluation we conducted.

While the infrastructure for growth and sustainability of activities to enhance nursing engagement in tobacco control has been developed, it is premature to estimate the direct impact on health and nursing practice for each nation. Several of the nurse champions started to outreach to nursing schools and nursing faculty, offering the educational programs to nursing students.

The team made all possible efforts to ensure that the educational activities across countries followed a pre-established, agreed upon protocol, but as with all human interactions, slight variations likely occurred.

Future directions

As the CoE continues to grow and expand, changes in nursing practice in tobacco control continue to be monitored. Additionally, system changes in healthcare institutions that facilitate nurses’ engagement in cessation interventions should also be monitored, such as the inclusion of tobacco assessment as part of the medical record in one Czech hospital, as the goal is to promote policy changes that provide access to evidence-based treatment to all patients who smoke. In Hungary, the program is expanding to reach all home health visitors and primary care clinics. In Romania, nurse leaders are engaging with schools of nursing and nursing students to promote education on tobacco dependence treatment. The establishment and maintenance of a variety of partnerships that could build a network in support of nurses’ engagement in tobacco control activities was, and remains, pivotal to the long-term success of the CoE as is the integration of nurses’ contribution into broader tobacco control efforts supporting the implementation of the FCTC.

CONCLUSIONS

We demonstrated the ability to cross geographical, sociocultural, economic and political differences to engage nurses in multiple countries in a common goal – the reduction of unnecessary death and suffering from tobacco use and exposure, through a Centre of Excellence coordinating the educational activities. The CoE was able to mentor and support nurse champions who are becoming tobacco control leaders in their countries.

The COE offers a model to build capacity, expand nurses’ role, and engage nurses to implement evidence-based interventions that will contribute to reaching global health and development targets. The International Council of Nurses has acknowledged the pivotal role that nurses will play in reaching the SDGs30, and nurses are in an ideal position for involvement in non-communicable diseases (NCDs)31. The CoE provides a model structure and mechanisms for dissemination that the ‘Nursing Now’ campaign32 can use. The CoE promotes nurses’ engagement in policy, addressing SDG through grass-roots mobilization, changes in nursing standards of practice and contributes to policy changes that facilitate smoking cessation.