INTRODUCTION

Tobacco consumption remains one of the most significant public health issues causing deaths, disease, and economic burdens1. Although in the United States tobacco smoking rates dropped by 5.4% in 2016 compared to the prevalence rate in 20052, many developing countries such as the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia (KSA) are experiencing an alarming increase in tobacco smoking among their populations3-5. AlBedah and Khalil5 reported that the KSA has lost 0.28 million lives and 20.5 billion US dollars due to tobacco smoking between 2001 and 2010, without accounting for smuggled tobacco.

Despite the tremendous efforts that the KSA is making to combat tobacco smoking4, researchers have conceded that the prevalence of tobacco smoking is alarming and warrants immediate actions from both Saudi policymakers and health professionals3,5,6. For instance, two national surveys, conducted in 2013 and 2018, found that the prevalence rate of tobacco smoking among the Saudi population was 12.2% and 21.4%, respectively3,6. This increase of 9.2% in tobacco prevalence within only a five-year period may indicate a poor evaluation of the current tobacco issue.

Saudi college students have shown a higher rate of tobacco consumption than the general Saudi population. A systematic review and a meta-analysis study, conducted during 2010–2018, indicated that the smoking prevalence among Saudi college students was 17%. The meta-analysis showed that the Saudi male smoking rate was 21% higher than the female rate7. Another review stressed the importance of monitoring tobacco consumption among youth before it reaches a level of economic and healthcare burden8. Alotaibi et al.7 provided an epidemiological context about tobacco smoking prevalence among college students in the KSA7.

Additionally, ample studies have investigated various determinants associated with tobacco smoking among Saudi college students7-9. However, no systematic review has analyzed those determinants systematically. Thus, the purpose of this systematic review is to synthesize and to assimilate the vast amount of information available on the determinants of smoking by Saudi college students. The outcome of this review is to offer a foundation for specific recommendations concerning future research, theory, and interventions aimed at reducing Saudi college students’ smoking behavior. Our research questions are:

What are the determinants/risk factors associated with tobacco smoking among Saudi college students?

Which study designs have been used to address the determinants of tobacco smoking?

Which theories (or models) have been previously used to explain students’ smoking behavior?

What statistical analyses have been used to determine whether risk factors were associated with smoking?

METHODS

The study followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines10. In this systematic review, the outcome of interest is tobacco smoking, which is defined as the inhalation of the smoke of burning cigarettes, cigars, and waterpipes. Smokeless tobacco and electronic cigarettes were excluded from the study, due to insufficient prior research of Saudi college students. Because we are interested in understanding the factors associated with smoking, we excluded studies that assessed factors associated with tobacco cessation or with secondhand smoking. In accordance with a previous study7, studies that recruited students from a college of medicine, pharmacy, applied health sciences, nursing, and/or dentistry were coded as health-related studies.

Search strategy

Two reviewers (SA and PD) independently searched for articles in four databases (i.e. PubMed, ProQuest, CINAHL, and Web of Science). These databases were selected due to either their comprehensiveness or their usage in previous research reviews7,8. The research was restricted to articles that were published between 2010 and 2019, in order to ensure the most up-to-date research studies of the topic. Key terms were established based on the objectives of this study and in accordance with the previous study7. Keywords were used to identify articles through the title or the abstract with no language restrictions (Supplementary file, Table S1). The investigators aimed to translate articles written in other languages (e.g. Arabic). Additional studies were added depending upon an investigation of each article’s reference page or an online citation of included articles. The research ended on 30 August 2019.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Articles were included if they: 1) reported exclusively determinants of tobacco smoking, 2) focused on college students in the KSA, 3) were published between 2010 and 2019, and 4) measured tobacco smoking as a dependent variable (i.e. outcome). Articles were excluded if they: 1) were conducted outside of the KSA; 2) were reviews, commentaries, presentation posters, brief reports or graduate theses or dissertations; 3) measured e-cigarettes or smokeless tobacco use, 4) were not full-text or original research studies; 5) measured tobacco smoking as an independent variable (i.e. predictor); or 6) assessed tobacco cessation or secondhand smoking.

Quality assessment

All of the included articles were evaluated or appraised using the modified Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE)11,12. Any article that scored between 12–15, 9–11, or 0–8 was considered to be of high, moderate, or low quality, respectively12. Two reviewers (SA and PD) separately scored each article. Then, they met to discuss any disagreement.

Data extraction and data synthesis

Using Excel software, two researchers (SA and PD) independently reviewed studies’ titles and abstracts and extracted those that satisfied the inclusion criteria. After determining their final eligibility, fulltexts studies were imported into NVivo software for data extraction. From each article, two researchers independently gathered data for: the location of study, the year of study, the population of study, survey types, the sample size, the type of tobacco smoking, study design, the use of theories (Yes or No), the type of statistical tests, and the sampling techniques. Determinates that were tested with the outcome variable (i.e. tobacco smoking) were collected. Due to a huge variation of coding determinants among previous studies13,14, we coded any tested determinant into one of three categories: individual, social, or environmental levels. Those factors that concern an individual, such as demographic characteristics (e.g. age, gender etc.) or psychological wellbeing (e.g. stress and depression) are coded as an individual level. The social level encompasses any social connection or bond with the individual, such as friends and family. The environmental factors are those that mediate the structure of the surrounding community, such as a physical setting or place, policy, or media. Factors that showed significance at the p≤0.05 level were emphasized in a table. This systematic review is IRB exempt and does not require approval.

RESULTS

Characteristics of included studies

Of the 300 studies, twenty-one met the inclusion criteria for this systematic review (Figure 1)9,15-34. The characteristics of the included articles are presented in Table 1. The majority (43%) of studies investigated only male smoking behavior, while 38% and 19% of the included articles addressed risk factors of smoking among both genders and females, respectively. Almost half of the included studies were conducted among health-related students, either in the city of Riyadh or in the city of Jeddah. Moreover, 76% of the included studies combined waterpipe and cigarette smoking in their research as one term (i.e. tobacco smoking). Two studies investigated only cigarette smoking18,19 and one addressed waterpipe smoking27. Two research articles did not define which type of tobacco smoking was being measured20,29. Twenty studies examined the determinants of tobacco smoking among Saudi college students, using a retrospective cross-sectional design and based on no particular theoretical framework. However, one study did utilize a longitudinal observational design (time 1 vs time 2), using two theoretical frameworks (i.e. social learning theory and social control theory)29. In all, 43% of the included studies utilized pre-designed questionnaires (Global Adults Tobacco Survey [GATS] or Global Youth Tobacco Survey [GYTS]). Despite the use of different sampling techniques (e.g. multi-stage sampling or random sampling) to recruit participants, 20 studies recruited participants from one campus. All of the included studies were written in English.

Table 1

Characteristics of included studies (N=21)

| Authors (year) | Gender of population (College) | Location | Sample size | Sample technique | Type of tobacco smoking | Survey type | Number of factors found significant |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mandil et al.9 (2011) | Both (All) | Riyadh | 6793 | Multi-stage | Cigarettes & waterpipe | GYTS | 7 |

| Abdulghani et al.15 (2013) | Female (All) | Riyadh | 907 | Convenient | Cigarettes & waterpipe | Self-developed | 0 |

| Al-Ghaneem and Al-Nefisah16 (2016) | Male (Ed., Sci., BA) | Majmaah | 301 | Multi-stage | Cigarettes, waterpipe & cigars | Not available | 1 |

| Al-Haqwi et al.17 (2010) | Both (Health: Medical) | Riyadh | 215 | Convenient | Cigarettes & waterpipe | GATS | 2 |

| Al-Kaabba et al.18 (2011) | Both (Health: Medical) | Riyadh | 153 | Convenient | Cigarettes | WHO | 2 |

| Almogbel et al.19 (2013) | Male (Three campuses) | Hassa & Buraidah | 467 | Convenient | Cigarettes | Self-developed | 5 |

| Almohaithef and Chandramohan20 (2018) | Male (All) | Abha (KKU) | 337 | Multi-stage | Not available | Not available | 1 |

| Al-Mohamed and Amin21 (2010) | Male (All) | Hassa | 1382 | Multi-stage | Cigarettes & waterpipe | GYTS | 6 |

| Alshehri et al.22 (2019) | Both (Health: Medical) | Tabuk | 287 | Random | Cigarettes & waterpipe | Self-developed | 4 |

| Almutairi23 (2016) | Male (Ed., Sci.) | Riyadh | 715 | Convenient | Cigarettes & waterpipe | Self-developed | 4 |

| Alswuailem et al.24 (2014) | Both (Health) | Riyadh | 400 | Convenient | Cigarettes & waterpipe | GATS | 4 |

| Ansari and Farooqi25 (2017) | Female (Health: Medical) | Dammam | 332 | Not available | Cigarettes & waterpipe | GYTS | 2 |

| Ansari et al.26 (2016) | Male (Health, BA) | Majmaah | 340 | Multi-stage | Cigarettes & waterpipe | WHO | 1 |

| Awan et al.27 (2016) | Male (Health) | Riyadh | 535 | Random Cluster | Waterpipe | Self-developed | 3 |

| Azhar and Alsayed28 (2012) | Female (All) | Jeddah | 310 | Not available | Cigarettes & waterpipe | GATS | 1 |

| Jiang et al.29 (2018) | Male (All) | Riyadh | 340 | Random Cluster | Not available | Self-developed | 3 |

| Koura et al.30 (2011) | Female (Lit., Sci.) | Dammam | 1020 | Multi-stage | Cigarettes & waterpipe | GYTS | 2 |

| Mansour31 (2017) | Both (Health: Dental) | Jeddah | 336 | Convenient | Cigarettes & waterpipe | Self-developed | 3 |

| Mahfouz et al.32 (2014) | Both (All) | Jazan | 3764 | Multi-stage | Cigarettes & waterpipe | GYTS | 3 |

| Venkatesh et al.33 (2017) | Male (All) | Buraidah | 199 | Convenient | Cigarettes & waterpipe | Self-developed | 0 |

| Wali34 (2011) | Both (Health: Medical) | Jeddah | 643 | Convenient | Cigarettes & waterpipe | GATS | 2 |

Quality assessment

The two authors (SA and PD) agreed on 298 items out of 315 with 94% agreement. The 6% (n=17) disagreement was resolved by further discussion. Overall, four studies maintained a high-quality score of 12 out of 15 points9,19,21,32. Seven studies showed a moderate quality of assessment, as they obtained a median score of 915,18,20,23,29-31. Ten studies were rated as poor quality, with a median score of 7 (Supplementary file, Table S2)16,17,22,24-28,33,34.

Determinants of tobacco smoking

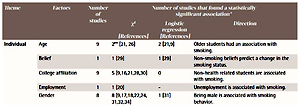

All but two studies found a range of risk factors that showed overall evidence for an association with tobacco smoking among Saudi college students. In our study, 21 risk factors were tested against the outcome variable (smoking behavior). Based on a bivariate analysis (i.e. the chi-squared test), 20 determinants were found significantly associated with Saudi tobacco smoking behavior, taking into consideration that some studies had tested more than one variable (Table 2). Seven studies indicated that some determinants were strong predictors of tobacco smoking among Saudi students, using multivariate analyses9,19,21,23,29,31,32. Although almost all of the included studies were done in a cross-sectional design, which inhibits the conclusion of any findings, results identified some possible risk factors associated with tobacco smoking.

Table 2

Determinants or risk factors examined by included studies

| Theme | Factors | Number of studies | Number of studies that found a statistically significant association* | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| χ2 [References] | Logistic regression [References] | Direction | |||

| Individual | Age | 9 | 2** [21, 26] | 2 [21,9] | Older students had an association with smoking. |

| Belief | 1 | 1 [29] | 1 [29] | Non-smoking beliefs predict a change in the smoking status. | |

| College affiliation | 9 | 5 [9,16,21,28,30] | 0 | Non-health related students are associated with smoking. | |

| Employment | 1 | 1 [20] | - | Unemployment is associated with smoking. | |

| Gender | 8 | 8 [9,17,18,22,24, 31,32,34] | 1 [31] | Being male is associated with smoking behavior. | |

| Income | 6 | 2 [19,25] | 0 | High income is associated with smoking. | |

| Knowledge | 5 | 4 [22, 23, 31, 34] | 2 [23, 31] | Low knowledge is linked to smoking status. | |

| Material status | 6 | 1 [9] | 1 [9] | Being single is associated with smoking. | |

| Religion | 2 | 1 [23] | 1 [23] | Low Islamic practice is associated with smoking behavior. | |

| Residence | 4 | 1** [21] | 1 [21] | Urban residence was a risk factor of smoking. | |

| School performance | 5 | 1** [19] | 1 [19] | Low GPA is associated with smoking. | |

| School year | 10 | 4** [9, 17, 22, 34] | 0 | Senior students had an association with smoking. | |

| Psychological issues | 1 | 1 [29] | 1 [29] | Stress is associated with tobacco smoking. | |

| Social | Friends’ substance use | 1 | 1 [32] | 1 [32] | Khat use (substance drug) is associated with smoking. |

| Teachers’ smoking status | 1 | 0 | - | - | |

| Parents’ education | 5 | 1 [24] | - | Students whose parents’ education is college or higher are associated with tobacco smoking. | |

| Family smoking status | 8 | 6 [9, 19, 21,24, 30, 31] | 4 [9,19,21,31] | Any smoker in the family was a strong risk factor for smoking. | |

| Friends | 7 | 7 [9, 18,19, 21, 23, 24, 32] | 5 [9,19,21,23,32] | Friends’ smoking status was a strong risk factor for smoking. | |

| Family occupation | 2 | 1 [18] | - | Students whose mothers are working or retired are associated with tobacco smoking. | |

| Environmental | Media | 1 | 1 [21] | 1 [21] | Students who were exposed to anti-smoking media messages were less likely to smoke. |

| Policy | 1 | 1 [29] | 1 [29] | Government’s efforts to control smoking was associated with a decrease in smoking. | |

Individual-level factors

Thirteen risk factors were coded as individual-level determinants. These risk factors were age, belief, college affiliation, employment status, gender, income, knowledge, material status, religion, residence, school performance (i.e. Grade Point Average [GPA]), school year, and psychological issues (i.e. stress). Gender was the single risk factor that was found significant in all of the eight studies performing the chi-squared test9,17,18,22,24,31,32,34. However, based on multivariate analyses (i.e. logistic regression), only Mansour31

found gender to be a statistically significant predictor of tobacco smoking among Saudi college current daily smokers31. Being male has statistically been shown to be associated with tobacco smoking among Saudi college students.Out of nine studies using bivariate analysis, five reported that being enrolled in non-health related colleges was statistically associated with tobacco smoking9,16,21,28,30. However, all of the studies testing college affiliation did not retain their significance in multivariate analysis9,21. Moreover, age was tested in nine studies but showed significance in only two studies21,26. In two multivariate analysis studies, older students were more likely to smoke than younger students9,21. Four of five studies testing knowledge of the harmful effects of smoking found a significant relationship with tobacco smoking22,23,31,34. Only two studies indicated that having low knowledge of the side effects of smoking predicted smoking behavior among students23,31. Seven studies demonstrated a statistically significant relationship between smoking status and being single9, unemployment status20, senior grade level9,17,22,34, low GPA19, urban residence21, and psychological issues29. Jiang et al.29 tested two theories that did not show any significance, except for one construct (belief) of social control theory. College students who have a belief about non-smoking practices were significantly associated with a decrease in tobacco smoking29.

Social-level factors

Six risk factors (i.e. friends’ substance abuse, teachers’ smoking status, parents’ education level, family smoking status, family occupational status, and friends’ smoking status) were coded in the social level and were tested for an association with tobacco smoking. It was determined that college students whose friends are current smokers are more likely to be smokers9,18,19,21,23,24,32. Five of the seven studies showed that friends’ smoking status predicted smoking behavior among Saudi college students9,19,21,23,32. Moreover, the presence of any smoker in a family was associated with college students’ smoking status9,19,21,24,30,31. In fact, four studies indicated that having any smokers in the family was a strong predictor for smoking among students9,19,21,31. An association between smoking status and students, whose friends use Khat (a substance drug)32, whose mothers are working or retired18, or whose parents are educated24, was observed. Teachers’ smoking status did not show any association with college students’ smoking behavior18.

Environmental-level factors

Media and policy were the two factors coded as environmental level. Al-Mohamed and Amin21 reported, using bivariate and multivariate analyses, that exposure to high media messages of non-smoking served as a protective factor against smoking, among Saudi college students. Meanwhile, Jiang et al.29 indicated that governmental policies on controlling tobacco use predicted the change from smoking to non-smoking behavior.

Three studies displayed a statistical significance of a risk factor in a table; however, the authors neglected to report this in their results and discussion sections21,25,27. Thus, we did not include them as significant factors, as we assumed that they could be typographical errors. Awan et al.27 showed, in a table, that school year, age, and residence were significant, but they did not mention their significance in their article. Ansari and Farooqi25 and Al-Mohamed and Amin21 neglected to mention the significance of GPA and school year, respectively.

DISCUSSION

This systematic review is the first known attempt to synthesize the current literature on the determinants of tobacco smoking among college students in the KSA. This research sets a foundation for current and future research on tobacco smoking among Saudi college students. Although our study did not restrict itself to any specific research design, we found a lack of qualitative and other observational designs (e.g. experimental, case-control, or cohort) that could assist in better understanding some of the risk factors of tobacco smoking among Saudi college students. In fact, Mandil et al.9 and Almutairi23 recognized the importance of conducting rigorous qualitative studies in order to understand the dynamics of Saudi college students’ smoking behavior. Moreover, our study discovered that there was poor utilization of theoretical frameworks to guide the research. Among the 21 included studies, there was only one study that utilized the social learning theory and the social control theory29. Theory-based research is needed to serve as a foundation for tobacco prevention and intervention programs14. Glanz and Bishop35 posit that, through the utilization of a theoretical framework, researchers will be able to understand both the determinants of health behavior and the process of health behavior change. Theory can guide research, can explain behavior, and can offer direction for designing and implementing interventions. In addition, all of the included studies relied heavily on retrospective methods of measuring tobacco smoking. Surveys are inclined to a number of biases and challenges, which could affect the results of the desirable outcome (studying smoking behavior). For example, several studies have found that selfreported measures of socially undesirable behaviors, such as smoking, are predisposed to underestimate the true amount smoked36, show digit bias (rounding to multiples of 5 or 10)37, and are subject to recall bias37. To minimize these biases, other collection methods of measuring tobacco smoking could take the form of prospective data collection, such as TimeLine Follow-Back (TLFB)37, ecological momentary assessment (EMA)37, or cigarette butt collection38. Finally, 20 studies recruited their participants either from one campus or from one college. Despite their sampling techniques (e.g. random or multistage sampling) within the campus or college, results could produce a limited application regarding their ability to be generalized to all Saudi university-age students. As of 2019, there are 30 universities, not including private institutions, distributed in different regions of the Kingdom39. Giving a snapshot of one campus or college is not necessarily representative of all KSA’s higher education students40. Therefore, future research should attempt to recruit participants randomly from different institutions in the KSA. A final observation is that the majority of articles in the literature (n=16) did not make a clear distinction between cigarette smoking and waterpipe smoking, especially when measuring cognitive factors such as perceptions, beliefs, attitudes, or knowledge. Some college students may believe that using a waterpipe is less harmful than smoking a cigarette41.

Risk factors of tobacco smoking

A basic tenet of understanding tobacco smoking among Saudis is to understand the underlying risk factors that contribute to the smoking problems. It has been argued that preventing youth from starting will reduce their chances of becoming smokers later in life14. The included studies tested many risk factors thought to be associated with Saudi students’ tobacco smoking. There were many more individual factors tested for an association with Saudi college students’ tobacco smoking than any other social or environmental factors. However, our study found that only four dominant risk factors (college affiliation, gender, knowledge, and school year) were statistically associated with Saudi students’ smoking, in four or more studies. Being male was found statistically related to smoking in all studies testing the gender variable. A notable explanation of the gender difference is that Saudi male college students could have fewer social restrictions than females. Saudi men enjoy social freedoms, such as being able to purchase tobacco and smoke publicly, whereas women are socially discouraged from doing so.

The family’s smoking status and friends’ smoking status were the major two social factors that showed a statistical relationship in smoking behavior, in six or more studies. Environmental factors were the least tested for an association with tobacco smoking, and were indicated in only two studies21,29. A noteworthy finding is that exposure to media messages related to non-smoking or to implementing a policy to control smoking was significant enough to influence Saudi students’ decision to maintain their non-smoking status or to change their smoking behavior, respectively21,29. Moreover, having a strong belief in non-smoking or practicing the Islamic faith produced significant evidence with changes in smoking behavior among Saudi university students23,29. Finally, friends’ substance abuse (Khat) was found to be a strong predictor of smoking tobacco among southern university students in the KSA32.

Limitations

Due to an enormous variation in data collection, study design, sample size, study population, and/or age groups among the included studies, we cannot conclude a causal relationship between these factors and smoking among Saudi university students, nor can we generalize the findings. Instead, we infer that some individual factors and social factors could play a role in influencing Saudi students’ smoking behavior given the data. Although the majority of included articles (n=16) categorized both cigarette and waterpipe smoking as ‘tobacco smoking’ in their research, special attention should be paid to the degree to which tobacco smoking (cigarette vs waterpipe) is more associated with each factor. Another limitation is that the search produced only articles published in English and in selected databases. Thus, we may have missed other studies that were published in other languages (e.g. Arabic) and were in other databases.

CONCLUSIONS

Four of the individual-level and two of social factors were able to demonstrate the association between college students and tobacco smoking. To better understand the current problem, future research should address Saudi students’ smoking behavior using other research methodologies (experiment or prospective observational) or using theoretical models to explain Saudi smoking behavior. Utilizing theoretical models as described above could assist in the development of intervention programs. Moreover, researchers should test other measuring approaches (TLFB or EMA37) to avoid certain biases and to arrive at an accurate estimate of tobacco smoking. More importantly, future research should make a clear definition and designation between cigarette and waterpipe smoking when measuring the association of certain factors (e.g. perceptions or knowledge), because the degree of each factor (e.g. knowledge) about tobacco could be different between cigarette smokers and waterpipe users41. Furthermore, we encourage future research to explore possible risk factors such as social, economic, environmental, biological, and physiological influences that may predict smoking behavior among Saudi college students.