INTRODUCTION

Smoking and repeated exposure to secondhand smoke are two leading causes of preventable, premature morbidity and mortality worldwide1-3. China alone accounted for approximately one-third of the global smoking prevalence in 20104,5, with 52.9% of males and 2.4% of females smoking regularly4, proportions that are reported to be increasing for men and decreasing for women6-8. Incidentally, awareness of smoking-related health risks is low in China, as three in four Chinese adults were found to have insufficient comprehension of smoking-related health risks5. Within China, smokers have also been found less likely to acknowledge the negative health consequences of smoking than Chinese non-smokers9. In Canada, there is a greater prevalence of smoking among Chinese immigrants compared to other Canadian immigrant communities10, and smoking is known to play an influential role within Chinese-Canadian communities10,11. Differences in smoking practice and prevalence exist between males and females in Chinese-Canadian communities12, similar to China4,13. The observed differences may be attributed to culturally rooted beliefs regarding the gender of a smoker as well as socio-environmental factors14. For instance, male smokers often obtain pro-smoking information from older male family members15, and views on self-reliance and social norms prevent full effectiveness of smoking cessation interventions16,17. In contrast to males, it is often deemed socially unacceptable for females to smoke18. These culturally influenced perceptions and gender-related differences should be considered when developing appropriate smoking cessation programs in an attempt to reduce the burden of smoking on the healthcare system, especially since Chinese immigrants currently comprise the largest ethnic minority group living in both British Columbia and Canada19,20.

In Canada, denormalization of smoking in Chinese-Canadian communities may enhance the effectiveness of cessation interventions among both adults17,21 and youth22. Enhanced consideration for socio-environmental factors and culturally influenced perceptions may enhance the effectiveness of future interventions23; however, the role that these factors and perceptions play in the promotion or hindrance of Chinese immigrants to Canada’s smoking behaviours and norms is not yet fully clear. Thus, our qualitative exploratory study aimed to ascertain Chinese immigrant smokers’ perceptions, attitudes, and beliefs regarding smoking as well as perceived barriers and facilitators to smoking cessation. We also collaborated with several key informants with extensive knowledge of the target communities’ smoking norms. A thorough understanding of community members’ and key informants’ perspectives and opinions may help to inform the design and implementation of culturally appropriate smoking cessation programs for Chinese immigrant smokers and may facilitate the development of culturally relevant and linguistically accessible educational interventions and materials for the target community.

METHODS

A qualitative exploratory study design was used to ascertain factors influencing smoking practice and smoking cessation within Chinese-Canadian communities from the perspectives of adult current smokers and key informants in the Greater Vancouver Area, Canada. Ethics approval for this study was obtained from UBC Office of Behavioural Research Ethics.

Participant eligibility and recruitment

Eligible participants were adult (≥19 years) current smokers (≥5 cigarettes per day for the past 30 days) of Chinese descent (Mandarin- or Cantonese-speaking), who had immigrated to Canada within the past 5 years or were the children of Chinese immigrants to Canada. Key informants were healthcare professionals (e.g. clinicians, educators), immigrant and smoking cessation-related researchers, policy-/decisionmakers, or program directors of local community organizations primarily serving immigrants. Key informants had extensive knowledge of cultural norms and practices pertaining to smoking and smoking cessation, and experience working with individuals from the target communities. Recruitment efforts were greatly enhanced through professional network referrals by key informants and collaboration with community-based agencies serving immigrants (e.g. SUCCESS [United Chinese Community Enrichment Services Society] and MOSAIC), Vancouver Coastal Health community organizations, physician referrals, advertising at community events/health fairs, and the work of our bilingual research assistants and community facilitators.

Study design

A multistage mixed-methods study was conducted from January 2013 to June 2014 applying a community-based participatory research approach. This approach was applied to involve community members, key informants, and relevant community organizations throughout study design and conduct to ensure enhanced consideration for the target communities’ cultural and linguistic needs. Prior to study commencement, 4 bilingual (English- and Mandarin- or Cantonese-speaking) community facilitators (2 males and 2 females) and 4 bilingual female research assistants were hired to recruit participants and to conduct interviews and focus groups; in addition, research assistants translated focus group audio-recordings from Mandarin or Cantonese to English verbatim. Both the community facilitators and research assistants were trained on approaches to participant recruitment, how to obtain informed participant consent, and how to conduct focus group sessions in a culturally relevant (with respect for cultural norms and practices) and linguistically appropriate (in a language accessible to all participants) manner to create a safe environment where participants could share their often personal thoughts and perspectives. Initially, a qualitative exploratory study was conducted with adult current smokers from the target communities and key informants. Focus groups were held with adult smokers from the target communities to ascertain perceptions, attitudes, and beliefs regarding smoking behaviours and practices, as well as to identify incentive factors or barriers to reduce or quit smoking. Key informants were interviewed or completed a survey interview on why individuals from the target communities began to smoke, the challenges facing individuals to quit, and culturally appropriate best practices to facilitate the cessation process. The perspectives and opinions of participants and key informants, and qualitative information obtained in a previous study23, served to inform the development of a study measurement tool in the form of a questionnaire that underwent validation and was applied in a cross-sectional study to assess beliefs and risk perceptions regarding smoking practices and cessation from the target communities. This paper summarizes the qualitative exploratory study’s findings from the initial participant focus groups and key informant interviews. The development process of the measurement tool and the quantitative results of the cross-sectional study are reported elsewhere11.

Focus group procedures and data collection

Focus groups were held with adult current smokers from the target communities and facilitated by a team of trained bilingual research assistants and community facilitators. Prior to consenting to participate, each group was provided details regarding the study (e.g. rationale, objective, etc.), what their participation entailed, and informed that the discussion would be audio-recorded for verbatim transcription and that any responses would be anonymized. Participants were then given an opportunity to ask questions, and, if they agreed to participate, signed a written consent form in their preferred language (available in English, Chinese Simplified, and Chinese Traditional). Focus groups were held in Mandarin, or Cantonese, and followed a semi-structured format in which research staff would pose a question or prompt and allow for subsequent discussions to take place. Participants were asked to share their thoughts and views on a number of environmental, cultural, and personal factors influencing smoking onset, continuation, and cessation. For example: ‘Have you tried to quit? If yes, what motivated you to quit?’. Please see Supplementary file, Document 1, for a full list of focus group questions and prompts. Focus groups lasted from 60 to 90 minutes. In addition, research assistants completed observation notes to help contextualize responses when being reviewed during analysis. At the end of each session, modest incentives were provided to each participant for compensation of time, travel, and parking expenses.

Interview procedures and data collection

Individual interviews were conducted with key informants, who were professional individuals/ clinicians who had experience working with immigrants from the target communities, conducting research in smoking-related fields, or providing services to members of Chinese communities in the Greater Vancouver Area. Interviews were held inperson or interview questions were provided online in a typed survey format to those unavailable for an in-person interview. In-person interviews were conducted by one member of the research team who initially provided the key informant with the same study- and confidentiality-related information detailed in the ‘Focus group procedures and data collection’ section, allowed for any questions to be answered, and subsequently obtained written consent. For online survey interviews, key informants were provided the written consent form, provided the study team’s contact information in case of any questions prior to participating, and electronically signed the consent form. In-person interviews followed a structured format in which a question was posed, the key informant would respond, and the interviewer would then proceed to the next question. The online survey consisted of the same open-ended questions as those posed during the in-person interviews. Key informants responded to open-ended questions regarding factors influencing smoking patterns, facilitators or barriers to quitting smoking for members of Chinese-Canadian communities, and practical components of and approaches to a smoking cessation program for the target community. For example: ‘Based on your experience, why do the people in your community start smoking (what causes them to pick up their first cigarette)? How do they start? – exposure, age groups, gender, etc.’. Please see Supplementary file, Document 2, for a full list of key informant interview questions and prompts. The key informant in-person interviews lasted between 30 to 45 minutes and were audio-taped for transcription, whereas online survey interviews were completed and returned to the research team. Research assistants also recorded observation notes during in-person interviews to allow for cross-referencing to contextualize quotes during data analysis. Key informants did not receive any compensation for participating.

Data analysis

Verbatim transcripts from group discussions and interviews, and typed responses to online survey interviews were systematically reviewed by two members of the research team (N.T. & J.S.) and cross-referenced with observation notes to provide additional context/background. An inductive approach to analysis was taken that employed a constant comparison methodology to coding, an approach in which data were manually coded and assigned to a best-fit node. If coded data could not be assigned to a node, a new node was created. The coders consistently reviewed and discussed codes, nodes, and categorizations. When disagreements occurred, another member of the research team (I.P.) reviewed the coded data, provided input, and helped mediate subsequent discussions to facilitate an agreement. Following establishment of nodes, thematic analysis took place through individual categorizations by N.T., I.P., and J.S, and subsequent discussions occurred to identify emergent themes across nodes. Constant comparison of emerging themes took place until no new themes emerged. Descriptive saturation was achieved when additional nodes and themes did not emerge from further analysis.

RESULTS

Thirty-five adult Chinese-Canadian current smokers (11 female and 24 male) participated in 4 focus group sessions. In addition, seventeen key informants (14 female and 3 male; 9 in-person interview and 8 online survey interview) were interviewed. Three central themes emerged from data analysis: 1) factors influencing smoking initiation; 2) factors affecting the continuation of smoking; and 3) factors promoting/ hindering smoking cessation. The identified factors were then separated into internal (e.g. beliefs, perceptions, attitudes) and external (e.g. environment, family, work) to capture the nature of the influence on participants. The following sections provide direct quotes from participants and key informants. (IP) is used to denote data obtained from key informants through in-person interviews, while (OS) is used to denote data obtained from key informants through online survey interviews.

Internal factors influencing smoking initiation, continuation, and cessation

Smoking initiation

Image

The ‘image’ of a smoker was mentioned by participants as ‘an adult’ or more ‘mature’ within their communities. A Cantonese female mentioned that within her community:

One female key informant (OS) agreed and explained a common misconception of smoking within the target community:

‘For women, adolescents and young adults, they pick up smoking mostly due to the misconception that smoking is a symbol of personal freedom and is associated with independence and charisma.’

However, whereas participants described the ‘role model’ image of smokers with reference to individuals who they knew, key informants perceived the image of smokers to be based on the media’s portrayal. A female key informant (OS) detailed:

Stress

Stress (home/family, school, workplace, immigration, relationship) was identified by most participants and key informants as a primary factor for smoking onset and continuation. Participants and key informants both described smoking as a way to relieve stress. Immigration stress played a role in participants’ smoking onset. From the experience of a male key informant (OS):

Smoking continuation

Cultural norms/practices

Participants and key informants agreed that smoking practices differed greatly between Western culture and the Mandarin and Cantonese cultures. A Mandarin male mentioned:

Likewise, a female key informant (OS) agreed:

‘[In the] Chinese culture it's impolite to say no when others offer you a cigarette at a group gathering.’

However, whereas participants primarily described smoking as a common day-to-day practice (e.g. sharing as a gift, smoking with friends), key informants had a more holistic view and focused on the role it plays in one’s perceived ‘status’, and the intergenerational manner in which it is passed down as a norm through ‘descending belief’. A female key informant (OS) noted:

Stress

Stress was also mentioned as one of the main reasons for participants continuing to smoke, especially stress related to adjusting to a new culture or social environment. A Mandarin male expressed:

‘Because there are language barriers…there is a lot of stress as you cannot communicate with others, which is why you smoke.’

In addition, a Mandarin female indicated:

Smoking cessation

Culturally-based gender differences

Participants and key informants agreed that in Chinese communities there is a cultural disapproval towards females smoking, and mentioned this stigmatization as a potential barrier to accessing cessation resources. A male key informant (IP) indicated:

‘Traditionally, Chinese women did not smoke since it was socially unacceptable, especially in public.’

The participants also mentioned the influence of these perceptions to create a primarily male smoking culture. A Mandarin female added:

However, whereas participants solely focused on the negative perceptions of female smokers, some key informants mentioned that smoking may be useful as a tool for women to succeed in a patriarchal business environment. A female key informant (IP) indicated:

‘To triumph in a male dominant society, smoking is an effective way to network and prove their worth.’

Additional quotes regarding internal factors from participants and key informants can be found in Tables 1 and 2, respectively.

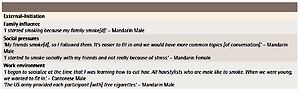

Table 1

Internal factors influencing smoking and smoking cessation, from the participants

Table 2

Internal factors influencing smoking and smoking cessation, from the key informants

Table 3

External factors influencing smoking and smoking cessation, from the participants

External factors influencing smoking initiation, continuation, and cessation

Smoking initiation

Family influence

Participants indicated that family members had influenced their smoking onset, and that smoking was a common activity amongst relatives. A Cantonese male stated:

A Mandarin female added:

‘Since I was born, my father was [a] heavy smoker and I am kind of growing up [sic] in the second hand [sic] smoking.’

A female key informant (OS) noted that within this community:

‘Usually first-time smokers start relatively young… they get their cigarettes through friends or older siblings who smoke.’

Both participants and key informants agreed that the pressure of trying to seem ‘mature’ in front of older family members influenced the initiation of smoking.

Social pressures

Peer pressure and the social influence of other smokers were mentioned by both groups as reasons why participants initially gave smoking a chance, coupled with the desire to ‘fit in’ with a group of colleagues or friends. A Cantonese male stated:

One Cantonese female mentioned:

A female key informant (OS) explained the culture’s distinct pressure to appease one’s elders:

Smoking continuation

Socialization tool

Smoking played a key role in individuals’ social lives, and participants mentioned that smoking served as a common ground within the culture. A Cantonese male stated:

A male key informant (OS) echoed this sentiment:

‘Smoking has been deeply integrated with Chinese social interactions through the acceptance of cigarettes as a traditional Chinese gesture of good will.’

Participants and key informants agreed that it is a social tool, and a female key informant’s (IP) perception of social smoking was concordant with many participants’ views:

Smoking cessation

Government and regulations

Some participants suggested that the Canadian government should increase anti-smoking rules and regulations. One Cantonese male suggested a law in which:

A Mandarin male had different thoughts, stating:

In addition, a participant suggested stopping the production of cigarettes. In contrast, key informants took a broader approach to enforcement. A female key informant (OS) noted:

‘One of the ways to help smokers quit is establishing various obstacles. For example, passing laws and legislations and enforcing them to maintain smoke-free environments in restaurants and other public areas.’

Key informants also focused on the importance of education as opposed to passing anti-smoking laws. For example, a male key informant (OS) noted:

Educational materials

Available smoking cessation resources and educational materials were deemed insufficient by some participants and key informants. Most of these individuals believed that this problem is more severe in China than in Canada. One female key informant (IP) noted:

A female key informant (IP) elaborated:

‘Smoking is not a disease that can be treated by takecure action. It involves a systematic action plan and continual behaviour modifications in smoking cessation.’

A few participants suggested that access to information or resources could be provided via social media platforms.

Family affection

Participants and key informants indicated that support and motivation from family members could facilitate cessation. Both groups mentioned that smokers would primarily be motivated to quit because of the harm done to loved ones (e.g. children, spouse, relatives), primarily through secondhand smoke. A Cantonese male participant stated:

‘If I focus on my kids then I would think about [the] big impact smoking [has] on the health of my kids.’

Likewise, a female key informant (IP) believed that:

‘We need to involve different stakeholders of the smoker in successful cessation. Examples would be family members, close friends, mentors, physicians… covering all aspects of smoking.’

Additional quotes regarding external factors from participants and key informants can be found in Tables 3 and 4, respectively.

Table 4

External factors influencing smoking and smoking cessation, from the key informants

Table 5

Practical recommendations for future research programs and interventions

DISCUSSION

To our knowledge, this is the first qualitative exploratory study to examine both internal and external factors influencing smoking patterns and behaviours among Chinese adult smokers in Canada. We identified relationships between socio-cultural or environmental factors and smoking patterns and behaviours. The most influential internal factors identified in our study were the social pressure from peer groups and family to smoke (primarily for male smokers), followed by stress as a dominant predictor of smoking for both genders. Participants also indicated that stress was often immigration-related (e.g. language and cultural barriers). Participants and key informants agreed that culturally rooted differences in smoking practice exist between males and females. We found that many male smokers had been pressured by an older male family member to begin smoking during their teenage years; however, they continued smoking to socialize. In contrast, female smokers often acted as ‘secret smokers’ due to a perceived negative cultural attitude towards them, which may have acted as a barrier to accessing smoking cessation resources or programs. Overall, smoking was perceived by both males and females as a socialization tool for males, and was commonly used to find a ‘common ground’ with others in both business and leisure settings. There was a general sentiment amongst participants that the Canadian government takes greater action against public smoking than the Chinese government, and as a result, they were less inclined to continue smoking in Canada. Both participants and key informants indicated that there exists a lack of smoking cessation materials and resources tailored to immigrants living within Chinese-Canadian communities.

Similar studies have evaluated Chinese-Canadian smokers’ perceptions and behaviours related to smoking and smoking cessation. Chinese female smokers have reported smoking in secret due to a generally negative perception in Chinese culture18. The perception variance between the gender of a smoker was one of our critical findings. Participants and key informants indicated that within Chinese-Canadian communities there is a stigma around female smokers; however, where participants almost exclusively highlighted the perceived negative aspects of female smoking behaviours, key informants also included that it may serve as a socialization tool in a maledominated business setting. Thus, females may refrain from seeking cessation assistance, or feel ashamed to share their cessation struggles, even with healthcare professionals. Increased efforts from the research community to further bridge the gap in understanding of Chinese female smoking behaviours and perceptions may facilitate an increase in gender-accessible support from care providers.

A self-perpetuating cycle exists between elder and youth male Chinese smokers. Studies suggest that having parents and siblings who smoke is a predictor for an individual to smoke24. Participants and key informants indicated that cyclical learning and obeying is a trans-generational process that often promotes a general cultural acceptance within Chinese communities. Moreover, family members, especially siblings, have been reported as a direct source of cigarettes for youth and facilitators of smoking behaviour among younger individuals25,26. Participants and key informants agreed that family members were influential in smoking onset and perceived younger male family members to be under pressure to smoke in order to appear more ‘mature’. They also agreed that positive influence from family members and a desire to reduce the harm of secondhand smoke on loved ones could play a preventative role in smoking onset or motivation to quit. Cessation professionals, therefore, might consider involving family members in a supportive capacity in smoking cessation programs.

Teenage or young adult members of the Chinese community have been found to be more prone to the peer pressure or social influence to smoke27,28, an external factor also identified by both participants and key informants. The perceived image of a smoker was that of being more ‘adult’ or ‘mature’; however, participants expressed their image of a smoker with reference to individuals they knew, whereas key informants believed that smokers from the target community based their image of a smoker on the media’s portrayal. Therefore, care providers and those working in smoking prevention should consider this difference in perception when incorporating social influence into cessation or prevention programs. In addition, Yang et al.28 found that around two-thirds of their study’s participants smoked with others, perhaps indicating the importance of social situations and peer influence in promoting smoking behaviours within Chinese communities. This finding was corroborated by participants and key informants, who implicated a desire to ‘fit in’ as a reason for youth to begin smoking.

An increased emphasis on not smoking in public could promote cessation for Chinese immigrants, an important issue reported by other studies29-32. Canada’s Tobacco Act prohibits the sale of tobacco products to youth (under 18 years of age)33; however, participants believed that the Canadian government should implement stricter antismoking regulations, as extreme as banning the production of cigarettes. Key informants proposed an alternative approach involving education and greater understanding of risk as opposed to increasing barriers to access. From our study and many others, we have learned that placing warning messages on smoking packages is less effective34,35, especially for younger smokers36, and direct education on the harms of smoking is not always effective37. Therefore, anti-smoking policies may consider stricter amendments and educational components. With regard to education, changing the cultural attitudes and perceptions towards smoking may require increased access to quality smoking cessation resources. Educating and empowering individuals with risk perception skills38,39, in particular youth, on the health risks associated with smoking might be a step towards decreasing smoking rates within the target communities. In addition, because smokers from the target community often start due to a perceived social/cultural norm, smoking cessation efforts may see greater effectiveness by implementing a group-based approach rather than individual quitting attempts; however, cessation professionals should continue to provide cessation support based on the individual’s reasons for smoking and motivations to quit.

Strengths and limitations

The main strength of this study was the communitybased participatory research approach. The perspectives of current smokers from the target community and key informants, both of whom had an understanding of Chinese-Canadian communities’ norms and practices pertaining to smoking and smoking cessation, were captured. In addition, the bilingualism of the community facilitators and research staff may have enhanced the communication between smokers during focus groups and created a safe environment for smokers to share their opinions. However, the generalizability of our study’s findings to Chinese immigrant smokers in the Greater Vancouver Area is limited due to the use of convenience sampling. Next, as focus groups were held with multiple individuals, social desirability biases may have influenced the participants’ responses. Although data were captured from 2013–2014, this study’s findings are likely still applicable to the target population in 2020, as health and smoking behaviours, which are influenced by culturally rooted factors, have been found to be intergenerationally persistent among Chinese smokers15,40. Additionally, more recent studies have identified similar culturally ingrained beliefs about smoking practice and cessation among Chinese-Canadian immigrant groups16,21, as well as other Chinese immigrant groups17,41. The constant comparison methodology applied during data analysis was reliant on the study team members’ subjectivity; however, triangulation between researchers and triangulation of data worked to mitigate this potential weakness. Finally, as some key informants were unavailable for in-person interviews, they responded to the interview survey. There may be inherent variability in how these individuals responded to questions compared to their response if they had completed an in-person interview.

Future initiatives

Our study’s findings may serve to direct and inform smoking cessation programs for Chinese immigrant smokers to Canada. Participants and key informants communicated the existence of culturally rooted perceptions regarding smoking and smoking cessation within Chinese-Canadian communities; therefore, it is critical that future initiatives apply a culturally relevant and linguistically appropriate approach to smoking cessation. At times, participants and key informants expressed differing viewpoints on factors affecting smoking onset, continuation, and cessation; therefore, it may be beneficial to consider the viewpoints of both when developing prevention or cessation programs and resources. In addition, the identified lack of available resources for members of the Chinese immigrant community highlights the need for community-based resources that are developed with input from key stakeholders and community members. During the development of future interventions, researchers and smoking cessation professionals should consider embracing approaches that focus on attitude, perception, and belief modification. Future interventions may also provide enhanced focus on the long-term consequences of smoking and may do so through a risk perception model of smoking cessation. Table 5 contains a collection of practical recommendations for future smoking cessation programs for the target communities based on the thoughts, ideas, and values presented by key informants during interviews and modified to fit the needs expressed by the participants during the focus groups.

CONCLUSIONS

This study ascertained internal and external factors influencing Chinese immigrant smoking and smoking cessation practices from the perspectives of current adult smokers and key informants. Smokers from Chinese-Canadian communities may benefit from linguistically appropriate and culturally relevant smoking cessation interventions. To enhance the effectiveness of smoking cessation interventions for Chinese-Canadian immigrant smokers, interventions should consider culturally-based smoking behaviours and practices that are often influenced by cultural perceptions, attitudes, and beliefs, while maintaining a patient-centered, individualized approach. Our study’s findings may inform the development of future smoking cessation programs and resources for the target community and our approach may be applicable to other ethnocultural or immigrant communities.