INTRODUCTION

According to the Global Adult Tobacco Survey (GATS) 2016–2017, 21.4% of India’s population uses smokeless tobacco products (SLT)1. Smokeless tobacco use consists of chewing paan (mixture of lime, pieces of areca nut, tobacco and spices wrapped in betel leaf), chewing gutka or paan masala (scented tobacco mixed with lime and areca nut, in powder form), and mishri (a kind of toothpaste used for rubbing on gums). India has one of the largest number and relative share of tobacco users in the world2. It has been estimated that 90% of oral cancer cases in India are attributable to tobacco use of any kind3. A review by Boffeta et al.4 estimated that more than half of all oral cancers in India are caused by SLT use.

Unlike smoked forms of tobacco, SLT relies on absorption of nicotine through the oral mucosa5. In terms of toxicity, SLT products are commonly thought to be less toxic than smoked products even though they are associated with many adverse health effects including nicotine addiction, oral lesions, oral and pancreatic cancer, and cardiovascular disease6. Many of these adverse health outcomes are attributed to chemical carcinogens present in smokeless tobacco products including tobacco-specific nitrosamines (TSNAs) and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons6. TSNAs are thought to be among the most important tobacco-associated carcinogens due to their toxicity and high abundance in SLT products7. Different TSNAs are formed from the reaction of alkaloids with nitrite8, and levels of available nitrite are influenced by nitrite-reducing bacteria that are known to be part of a variety of bacteria, or microbiota, associated with tobacco products9.

SLT manufacturing in India falls into two categories: registered/organised and unregistered/unorganised. The estimated share of SLT production by the unorganised sector was 11% in 201110. Further, different SLT products manufactured in India undergo various processes of curing and mixing. Plain chewing tobacco is sold in sachets along with a pack of slaked lime which the user can mix. Gul (tobacco containing dentifrice) is a dry powder-like tobacco preparation made using fine tobacco leaf dust, molasses, lime, and red soil. It is then packaged into plastic sachets or tin boxes. Gutka is a wet non-perishable paan substitute, commercially manufactured containing areca nut, slaked lime, catechu, sun dried tobacco leaves, flavourings, and sweeteners. Loose locally sold tobacco leaves are manufactured using an air-curing process. Most products are sold in plastic packaging to ensure longer shelf life. Each step tends to be a potential inception ground for contamination as there are no stipulated guidelines for quality control and avoidance of microbiological contamination of tobacco products.

In 2010, to curtail environmental effects of tobacco product packages, directions were issued to ban the sale of tobacco products like gutka, tobacco and paan masala in plastic pouches. The Ministry of Environment and Forests finalised an enforced this regulation by March 2011. They are packed in various sizes and materials including plastics and paper packaging, stored in differing climatic and geographic conditions at various tobacco kiosks across the country2.

Microbiological contamination of SLT along with the impact of varying climatic and geographic conditions might pose an additional risk by altering the nature of the intended constituents of the packaged SLT product. Further, microbiological contamination might contribute to the conversion of nitrites and alkaloids into TSNAs, which are major carcinogenic agents. Hence, the present study was conducted with the aim to investigate bacterial contamination of commercially available SLT products and the types of bacteria that could be cultured from them.

METHODS

Product sampling

The study was conducted in two phases. The first phase was the collection of commercially available SLT products followed by a second phase that included microbiological analysis of the collected products. Ethical clearance was obtained from the Institutional Ethical Review Board before product analysis.

In our study, we have included only the SLT products manufactured by the organised sector. The city of Delhi is geographically divided into 5 zones, namely North, South, East, West and Central. The Central zone of Delhi was chosen based on convenience for collection of samples. A single investigator collected commercially available SLT products from tobacco shops located in the Central zone till no new products were found. The study was conducted in October 2018.

The current study included a total of 22 products including 7 brands of paan masala, 7 gutka, 6 khaini, and 2 tobacco containing dentifrices. Following collection, the products were identified, noting the batch number and date of manufacture if mentioned.

Sample analysis

For the second part of the study, all samples were transported and stored at room temperature prior to examination. The purchased products were then placed in a UV chamber for 30 minutes to ensure decontamination of the outer surface of the packets. In addition, all laboratory tools that were used during experiments were sterilized by autoclaving and flame sterilized immediately prior to use.

One gram of each product was dissolved in 10 mL of normal saline solution. After appropriate mixing, samples were centrifuged and cultures prepared by spreading 0.1 mL of each sample on different media and incubated for 48–72 hours at 37oC. The number of estimated colony-forming units (CFU) for each sample was counted. Discrete colonies of aerobic bacteria were sub-cultured for purification by streaking in fresh solid media11.

The following media were used as per the American Public Health Association (APHA 1985)12 and World Health Organization (WHO 1997)13 guidelines.

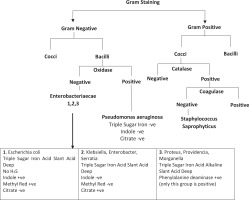

Further identification of isolated bacteria was made by gram staining and biochemical tests (oxidase test, urease test, coagulase test, Indole production test, and citrate utilisation test). These tests were performed according to Finegold and Baron14. A modified summary of the testing performed is provided in Figure 1.

RESULTS

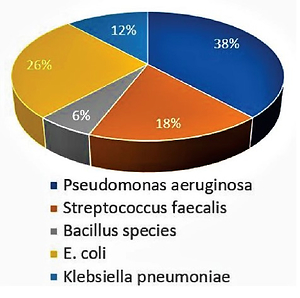

A total of 22 brands of SLT products were analysed for bacterial contamination using culture and incubation for 48–72 hours. All 22 brands of SLT were found to have bacterial contamination. The most commonly isolated bacteria were Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Streptococcus faecalis, E. coli, and Klebsiella pneumoniae (Figure 2).

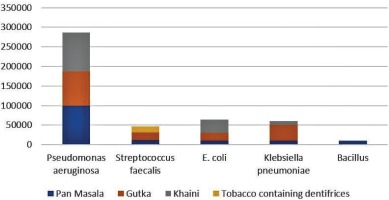

Of the 4 types of SLT products analysed, all brands of gutka were found to have the highest colony-forming units followed by plain tobacco, paan masala and then by tobacco-containing tooth powder. The distribution of the isolated bacteria varied across brands, shown in Figure 3. The distribution of the five most commonly isolated bacteria, among four categories of SLT products, differed across products and bacteria. Pseudomonas aeruginosa were the most commonly isolated bacteria with a mean CFU of 0.9×105. This was followed by E. coli, and the least commonly isolated bacteria being Bacillus subtilis.

DISCUSSION

Our study identified bacterial contamination of SLT products in India. The microbial content of SLT products placed in the oral cavity for long periods could be a health threat, especially to tobacco users who are immunocompromised. Long-term use of oral SLT has been associated with the development of oropharyngeal and upper respiratory-tract cancers and is a risk factor for cardiovascular disease and adverse reproductive outcomes15,16. In addition to the carcinogenic effects of SLT, the TSNA content of these products is associated with reported oral adverse effects including gingival recession, caries, staining, and abrasion17.

A total of 22 SLT products available in the market were analysed for contamination using bacterial culture. The number of brands to be included was based on previous studies conducted on SLT products in countries other than India18-20. All products were found to be contaminated with bacteria. This observation is particularly remarkable considering a previous report suggesting SLT products are microbiologically safe and stable21 — the results of the present study question the microbiological safety of SLT products available in the Indian market.

Tobacco, like any other agricultural product, undergoes processes of cultivation, harvesting, processing, and packaging. During the cultivation of tobacco, bacteria are present at approximately 105 organisms per gram of leaf material. At harvest, tobacco is not generally washed, thus leaves with deposited microorganisms and agricultural chemicals will be processed, and the contaminants will be present in the final product. During the subsequent curing step, the tobacco leaves are dried and bacteria, which proliferate to levels 10 to 20 times higher than on the growing leaf22, begin converting the nitrate present in the plant tissue to nitrite, a process called nitrate reduction. Once nitrite is produced, a chemical process of nitrosation occurs in which nitrite reacts with tobacco alkaloids to generate TSNAs23. Amine compounds, other than tobacco alkaloids, can also react with nitrite to form nonvolatile N-nitrosamines, volatile nitrosamines, and N-nitrosamino acids24,25.

The most commonly isolated bacteria from SLT products were Pseudomonas aeruginosa. The results of this study are similar to those of studies conducted in other parts of the world10,26. The bacteria isolated included Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Streptococcus faecalis, E. coli, Klebsiella pneumoniae, and Bacillus subtilus. This result is similar to the reports of Rubinstein and Pederson27, Ayo-Yusuf et al.28, Alsaimary et al.19, Okechi et al.29, Onuorah and Orji30, and Tyx et al.31, who reported the detection of some of these isolates, in contrast to the report of Ahamed32 who mainly found Bacillus species. The health risks associated with most of these bacterial isolates have been reported by Hardy et al.33. Factors such as lack of proper heat treatment during the fire-curing process of raw tobacco leaves can also produce contaminated products, especially if the leaves were infected as reported by Szedljak34. The hygroscopic nature of dried tobacco leaves and snuff was previously suggested to create a suitable environment for the growth of contaminating microorganisms35. Some of these might be important in the fermentation of raw tobacco leaves to produce the desired flavour. In contrast, the varieties of bacteria in the current study are not normal flora of tobacco but mainly of human origin and could be thought to have resulted from human contamination. Some of these microorganisms have been reported as potentially pathogenic to humans36.

The microbial populations that contaminate SLT products across the pre-processing, processing and post-processing lines may impact negatively on the health of SLT users due to their pathogenic potentials. The bacteriological examination of locally sold SLT products in Delhi revealed a microbial burden when compared with stipulated guidelines for microbiological food safety given for various food products.

WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (Articles 9 and 10) provides guidelines for the regulation of contents of tobacco products. However, the guidelines give no direction for microbiological contamination of finished tobacco products. In India, the Food Safety and Standards Authority of India (FSSAI) is responsible for protecting and promoting public health through the regulation and supervision of food safety. However, under various rulings given by the Judiciary various SLT products including paan masala do not come under food and are solely governed by the Cigarettes and Other Tobacco Products Act (COTPA) and associated laws. Unfortunately, the COTPA does not provide any microbiological standards or stipulated levels for the already harmful tobacco products. The Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of India, has made major strides and has successfully launched the National Tobacco Testing Laboratories across the nation at Noida, Mumbai, and Guwahati. This would aid in the monitoring of tobacco product constituents and regulating the same in the future.

Limitations

The present study has some inherent limitations. In our study, we could include only a few locally available packaged SLT products, limiting the information that could be collected. The methodology could be further strengthened by collecting samples of varying batches of the same product, collected through different seasons of the year. This would have shed light on the seasonal changes in the microbial contamination of the SLT products. Also, since all the samples were collected from a convenient location, the effect of varying geographical location of production could not be taken into account. Only aerobic bacteria were assessed as part of this study, leaving a plethora of other contaminating organisms still unidentified. Future studies with greater number of brands and batches should be conducted with advanced PCR techniques for the identification of the contaminating microbes. This study also could not assess the products manufactured from unregistered tobacco product producers, which in itself is an ever-booming elusive industry.

CONCLUSIONS

This study was undertaken to gain understanding of the bacterial populations that may be present in SLT products. Bacterial populations in these products need to be monitored for the protection of public health, and for the FSSAI and COTPA, as this should be incorporated under new regulations of tobacco products manufacture. One of the potential risks for SLT users is that the products could act as carriers of pathogenic or opportunistic microorganisms that might culminate in the development of infectious disease. Since most SLT products are typically held for extended periods in close contact with the oral mucosa, it becomes a matter of concern. The development of microbial metabolic by-products that might be harmful to consumers, such as microbial toxins and carcinogens, could be an added potential risk associated with microbial contamination. This study has raised and assessed the issue of bacterial contamination of packaged SLT products, but as this study was the first of its kind conducted in India, much remains shrouded due to lack of research initiatives on this issue. Owing to the lack of regulations on the production of SLT products, users might be subjected to a greater health hazard, especially those who are immunocompromised.